Running injuries suck. We all know that. However, just because you’re injured doesn’t mean you can’t continue training for that upcoming race. In this article we’re going to explore the theoretical and practical aspects of cross training for injured runners so that you can recover quickly from your injury and be fit enough on race day.

Cross Training for Injured Runners

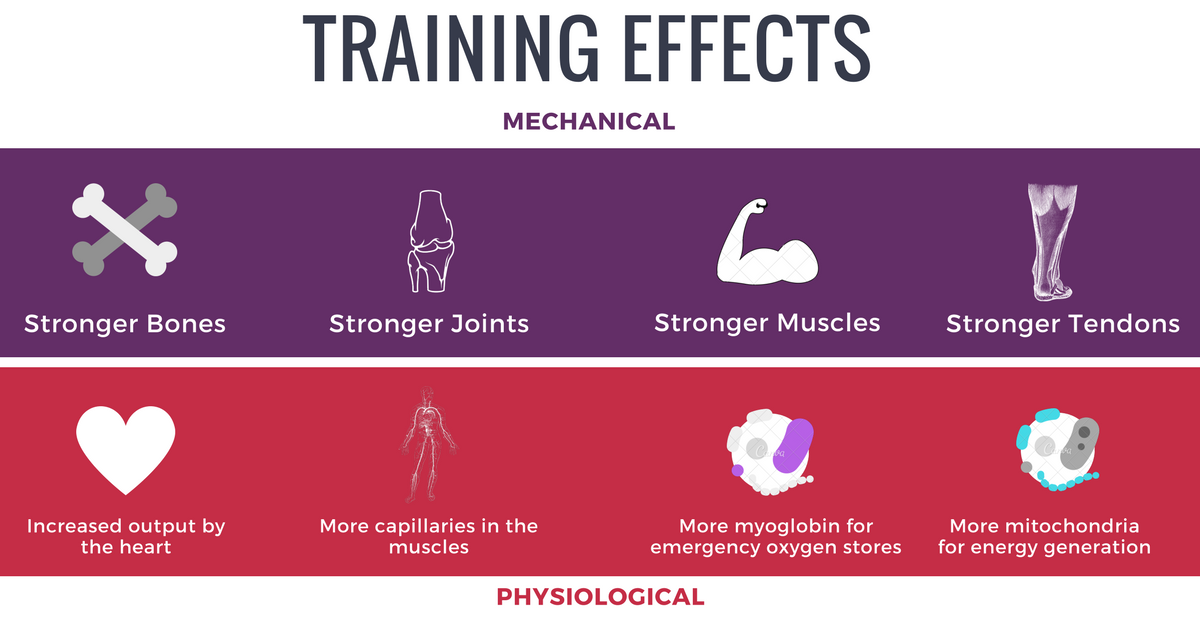

Running is a form of training for the body. As you run regularly you train your body to be able to run for longer without breaking down. This training effect is the result of the body’s inherent ability to adapt to the stresses placed upon it. These stresses can be categorized as physiological and mechanical.

Physiological Stress

Anything that causes an increase in breathing and heart rate we can think of as a physiological stress. We often substitute the phrase “cardio” here when we are talking about this kind of stress. It’s when we are doing something that causes us to breathe harder.

If we put our body under this kind of stress regularly then it will adapt and become more able to tolerate that stress in the future. A beginner runner may only be able to sustain a 6:00 min/km pace for a few minutes at first. As the runner becomes fitter by training regularly, their body will adapt and they could potentially sustain that pace for many hours.

The reason is that the body makes certain adaptations in response to that physiological stress. I talked about these adaptations in more detail in my article How to Run Slow to Race Fast but to summarize the body will:

- Increase the output of the heart by making the heart muscle bigger

- Create better capillary networks to get more blood to the muscles

- Increase the myoglobin content of the muscles to provide emergency oxygen stores

- Increase the number and size of the mitochondria to allow better energy production in the muscles

All these things will make a “fitter” runner. This is a big part of training, you need to get “fitter”, but that’s not the only thing you need.

Mechanical Stress

Anything that applies a physical force or load to the body we can think of as a mechanical stress. We often substitute the phrase “strength” when we are talking about applying a mechanical stress to the body. This is when we are loading the tissues of the body in some way. That might mean lifting weights or moving something heavy but it can also mean just standing up, walking or running. All of these activities apply a mechanical stress to the body’s tissues. A tissue is basically a collection of similar body cells. Muscles, bones, tendons, ligaments, skin, fascia, cartilage, all of these things are tissues.

All living tissues will adapt to the mechanical stress applied to them. If we regularly load our muscles we apply a mechanical stress that they will adapt to. With repetition, the muscle will become stronger. Here again is that training effect. However, it is not just the muscles that will adapt to the mechanical stress. Bones, tendons, skin, ligaments, cartilage etc. they will all adapt.

This also applies to bones. When you load your bones regularly they will adapt and become stronger. When astronauts go into space they will suffer from Spaceflight Osteopenia, which is when bones lose density in low gravity environments. This happens because they can’t load their bones properly.

The same thing applies to tendons. Tendonopathy (aka tendonitis) occurs when the tendon is not strong enough to tolerate the mechanical stress placed upon it. In recent years we have made huge progress in the rehabilitation of tendon injuries by moving away from offloading strategies (like rest) and toward loading strategies like strength training (Malliares 2013). Now we focus on regularly loading the tendon during rehabilitation to force it to adapt to the mechanical stress. The tendon responds to the stimulus by becoming stronger and able to tolerate more stress/load in the future.

We also see similar changes in joint cartilage. This is the cartilage in our joints that provides a smooth surface so our joints can slide easily as they move. Breakdown of this cartilage over time is referred to as Osteoarthritis. In recent years, it has become more apparent that joint cartilage will adapt to regular mechanical stress in the same way other tissues do. Regular loading of the joints through walking, running, weight training etc will cause the cartilage to adapt to the stimulus and become stronger (Musumeci 2016).

Even our skin adapts to mechanical stress. I remember getting some pretty nasty blisters when I took up tennis a few years ago. After a few weeks the skin on my feet had toughened up and I could play for hours without any blistering. The skin on the bottom of my feet had adapted to the mechanical stress applied to it.

Training Effect

When we run regularly our body will adapt to both types of stress, physiological and mechanical. In response to the physiological stress (cardio) we will become fitter. In response to the mechanical stress (load) we will become stronger. These are two types of training effect.

If we are training for a race, the physiological stress of the training will force our body to become fitter so we can run faster, longer. The mechanical stress of the training will force our body’s tissues to become stronger so they don’t get injured as we run.

The trouble with injuries is that they force you to stop training and you lose both types of training stimulus, physiological and mechanical. You have removed the physiological stress of the harder breathing while running but you have also removed the mechanical stress of impacting the ground as you run along.

When you are injured you will almost certainly have to reduce your training load in some way. Say you develop knee pain while training for a half marathon and the pain gets really bad if you run more than 3k. You can’t just ignore it and do the 15k long run your training program has scheduled for you.

You will need to reduce the mechanical stress on the knee by reducing the running volume. However, you don’t want to reduce the physiological stress on the body as you need to continue to gain fitness. So how do we achieve this?

Matched Intensity Cross Training

The goal of cross training for injured runners is to reduce the mechanical stress on an injured tissue without reducing the physiological stress on the body. In this way you will continue to gain fitness so that you “have the lungs” to get you round on race day. In order to continue to develop your physiological (cardio) fitness we are going to use some form of cross training.

You will also need to rehabilitate the injury by managing the mechanical stress placed upon the injured tissue. For more information on that I would recommend reading these two articles:

Adaptation: The Secret To Running Injury Prevention and Treatment

How to Use Running to Treat Overuse Injuries

For the rest of this article, we are going to focus on how to continue to progress the physiological stress in order to make you fitter. In effect, you will still be training for the race, just not by running.

To achieve this we are going to use a concept I call Matched Intensity Cross Training. During a typical training program for a race you will do running workouts at certain intensities for certain durations. You want to “recreate” the physiological stress of your running training program so you continue to gain fitness.

You are unable to run but you don’t get any pain from cycling, aqua jogging or elliptical training. You are going to use these as your cross training and you are going to match the intensity of your original running training program. The process is very simple:

- Look at your training program for the upcoming week

- Estimate how hard you would be working on that run (intensity)

- Estimate how long each run will take (duration)

- Do a Matched Intensity Cross Training workout for that duration at that intensity (cycling, aqua jogging or elliptical)

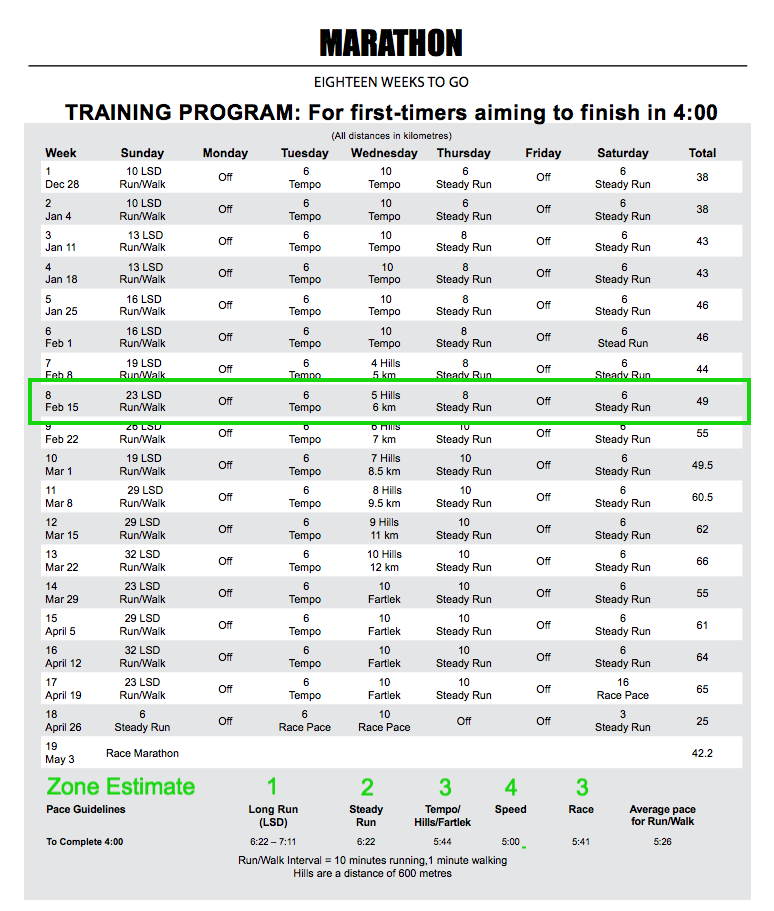

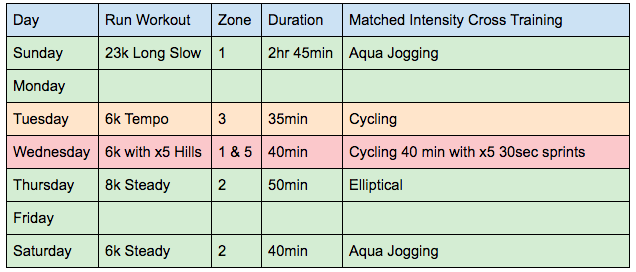

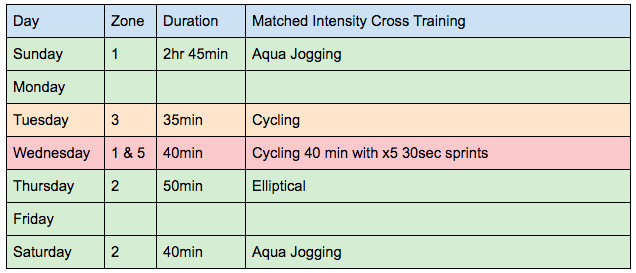

Let’s use the Running Room half marathon training program for example. Say you got injured at week 7 and you are unable to continue running. You are going to look at week 8 and try to recreate the physiological stress of week 8 using cross training. In other words we are going to use Matched Intensity Cross Training to “recreate” week 8.

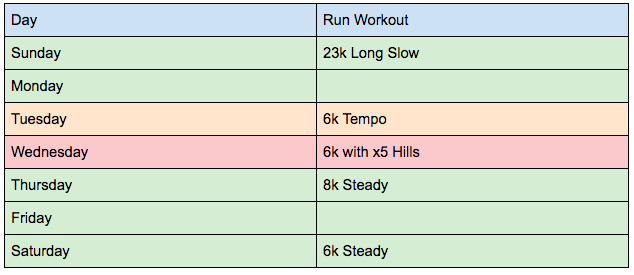

Week 8 looks like this:

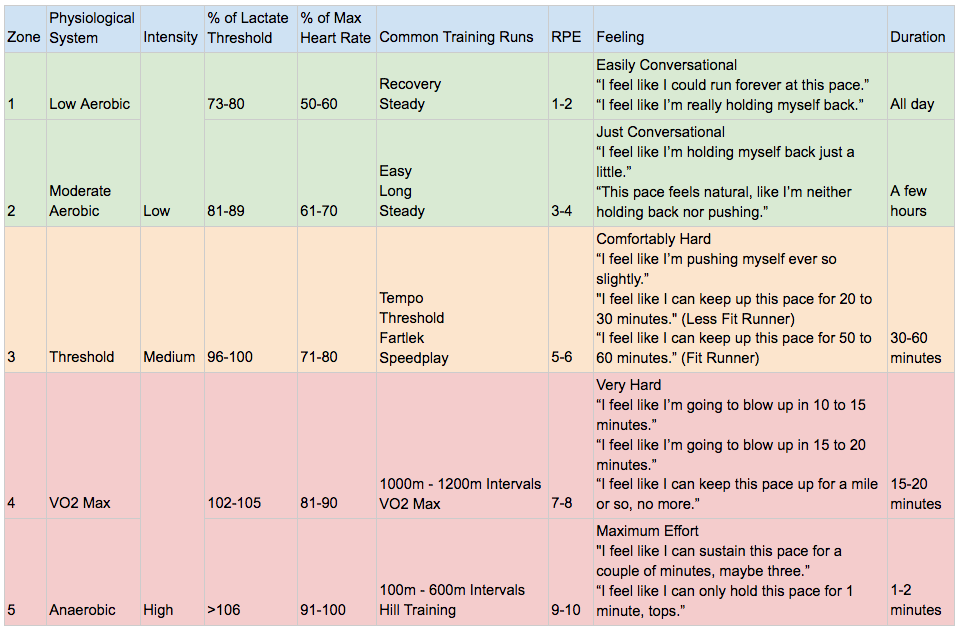

We can use the table from my Running Intensity Guidelines article to estimate which Training Zone each run is in. If you find all the talk of ‘zones’ and stuff too technical just think green is easy, orange is moderate and red is hard in terms of effort level. Here’s the table to help you estimate the training zone of each run:

Now we are going to estimate the training zone for each of the runs in week 8:

Then we can estimate the duration of these runs in minutes/hours (let’s say you were preparing for a 2-hour half marathon as this program suggests):

Now we just recreate the intensity of these workouts using one of the cross training methods or a combination of them:

Your new training plan for week 8 looks like this:

This all sounds a bit complicated when it’s written down but it’s actually really easy. Just follow the 4 step process:

- Look at your training program for the upcoming week

- Estimate how hard you would be working on that run (intensity)

- Estimate how long each run will take (duration)

- Do a Matched Intensity Cross Training workout for that duration at that intensity (cycling, aqua jogging or elliptical)

In Summary

Regular running training places both physiological and mechanical stress on the body. The physiological stress of breathing harder makes us fitter. The mechanical stress of loading the body’s tissues makes us stronger.

When we get injured we need to reduce the mechanical stress on the injured tissue but we want to maintain the physiological stress on our body so we continue to get fitter. We can do this using Matched Intensity Cross Training as described above.