Subscribe to The Adaptive Zone Podcast…

Jessie had originally come to us because she was having trouble with her plantar fascia. We managed to fix that within a couple of months and get her back to trail running. Then she set her sights on a 50k race.

Training went well and we were both pleased to see that the plantar fascia held up just fine. We used back-to-back trail runs at the weekend to help build up her muscular endurance without irritating the plantar fascia.

The week of the race we reviewed her training and we were both feeling confident that she was going to have an awesome race.

That’s not how it went.

A few kilometres into the race Jessie’s IT Band started to hurt. By the time she hit 18 km, it was hurting so bad on the downhill sections that she had to walk. Being the type of woman she is, Jessie didn’t let that stop her. She hobbled her way through the next 30 km and managed to finish the race.

But it was a miserable day.

We debriefed the following week, onceI’d had a chance to pour through her training data and the metrics from the race.

I’d messed up.

I realized what the problem was.

For her trail runs, Jessie and I had discussed the importance of getting on trails that mimicked the elevation profile of the race itself. Jessie had done this very diligently, for the Saturday run.

On Saturdays, Jessie would carve out the time away from the kids to get out to a kind of mountain nearby where the trail had a ton of elevation gain.

On Sundays however, Jessie would do a route near her house so she didn’t need so much time away from her family. It was a trail run, but much flatter than the race would be.

That was the problem. Her IT Band didn’t get enough exposure to the downhill to toughen up enough. So on race day, it wasn’t ready.

She didn’t have enough resilience in the IT Band to tolerate the more extreme trails. The stress on the IT Band was more than it could tolerate, so it became irritated and painful.

Elevation Change

Exposure to elevation change is the most important thing for ultra runners looking to avoid or get rid of knee pain.

It also happens to be the most inconvenient.

That’s because for most of us with jobs and kids, getting out to the mountains to spend half a day running up and down hills is kind of a pain in the butt. So lots of ultra runners will do 80 or 90% of their training on trails near their house.

Unfortunately (because most people don’t live in the mountains) these local trails usually have very little elevation change. Runners end up logging enough horizontal miles during their training, but not enough vertical.

When they do have the chance to get out to the mountains for a training run, they want to take advantage of it. So they do a super long run or two/three days of long runs. They have enough physiological fitness to do this, unfortunately, they haven’t built up the mechanical resilience to tolerate all that downhill

So something starts hurting, usually the patellofemoral joint or the IT Band – this is what happened with Jessie.

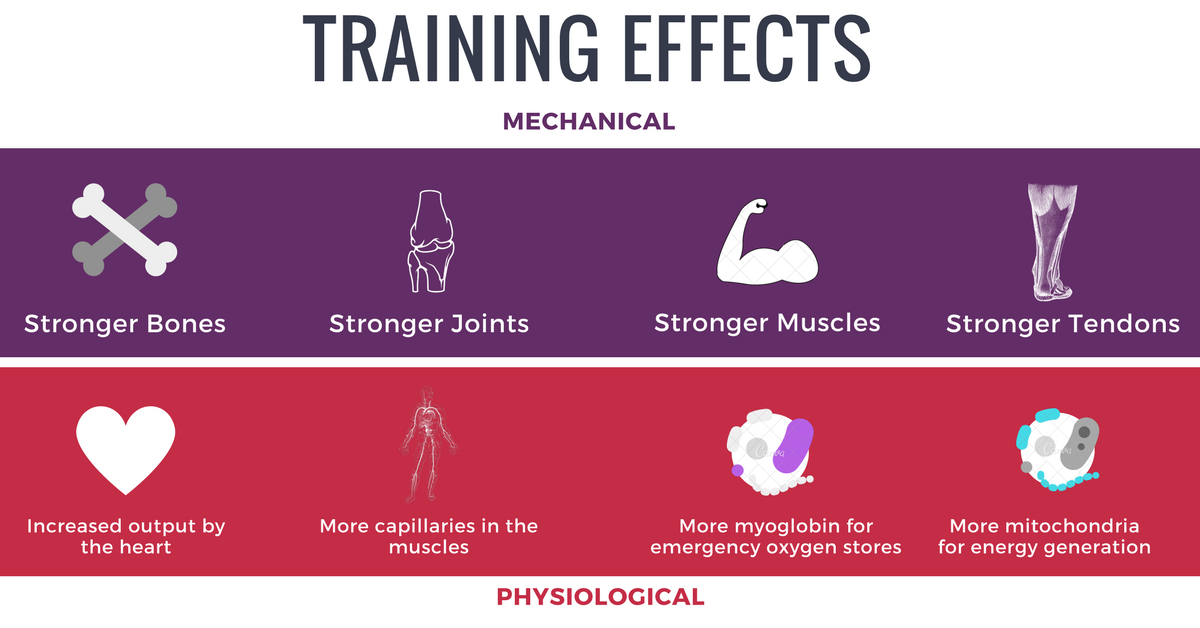

Physiological fitness is your cardiorespiratory and muscular capacity. Mechanical resilience is how much pounding your joints, bones and connective tissues can handle.

To acquire the mechanical resilience to run ultra trail races, you need to train on terrain that mimics your target race for at least two-thirds of your training runs.

Put simply, if you want to race very steep trail races, you need to toughen up your knees on steep trails. But, we can be more sophisticated than that by considering the Rate of Elevation Change.

Rate of Elevation Change

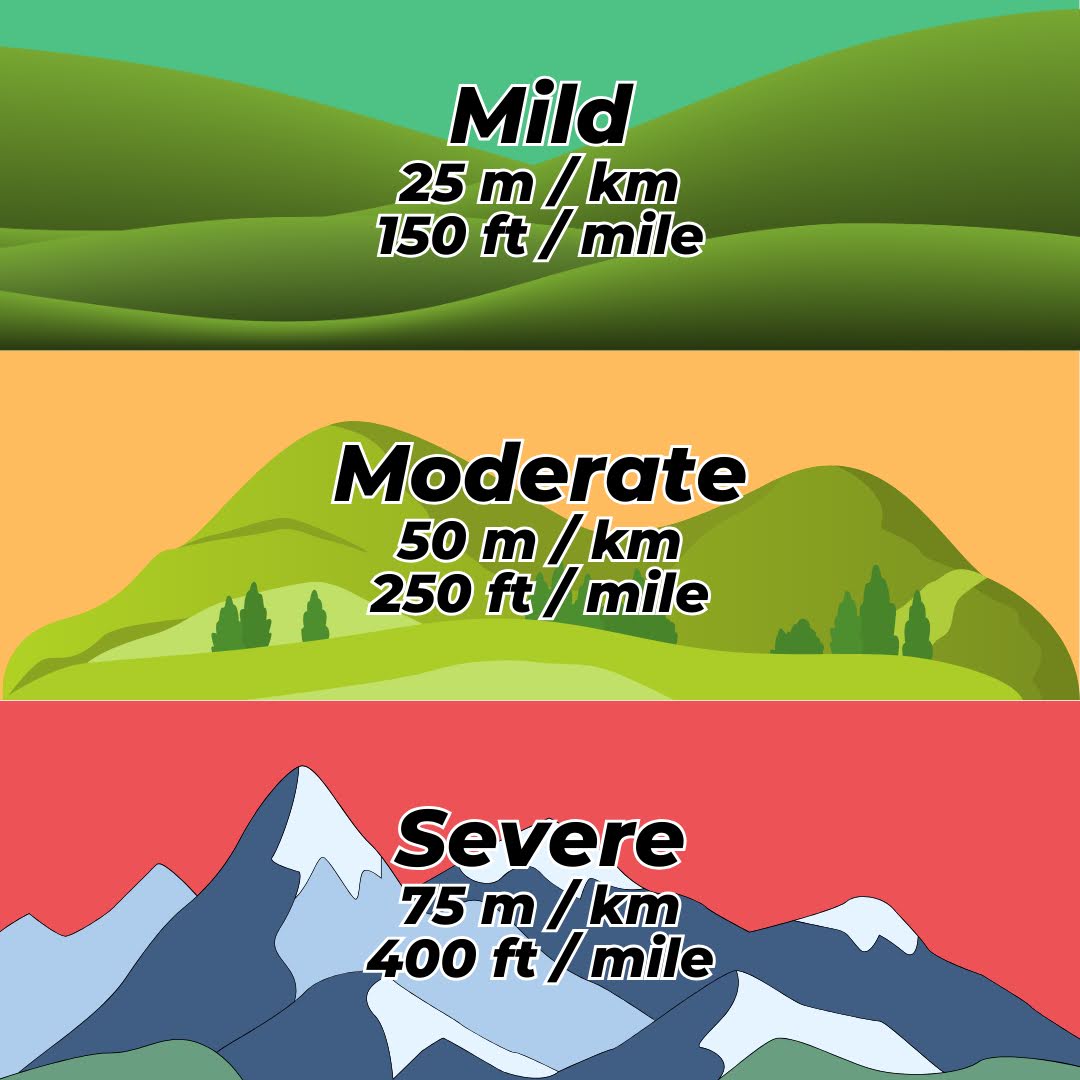

The Rate of Elevation Change is how much up and down you go per mile (or km).

Rate of Elevation Change = (Elevation Gain + Loss) / Distance

For example, Western States 100 is 18000 ft of elevation gain and 22,000 ft of loss. So we add those two together to get the total elevation change of 40,000 ft. Then we divide that by the number of miles covered to get the Rate of Elevation Change at 400 ft/mile.

I devised a simple system to classify your race as mild, moderate or severe in terms of Rate of Elevation Change.

Then we look at our chart to see that 400 ft/mile is just coming in as a Severe Rate of Elevation Change. Now we’re going to do two-thirds of our runs on trails that have a Severe Rate of Elevation Change.

That will give our bones, joints and connective tissues enough exposure to adapt. This will make them tougher and more resilient and protect them from injuries like PFPS and ITBS.

But what if you already have PFPS or ITBS?

Then graded exposure to trails with the type of Rate of Elevation Change that you want to do will be a key part of your recovery.

That being said, we usually do this later in your recovery, once we’ve established a baseline level of mechanical resilience. As a general rule of thumb, we’re not going to get you targeting specific moderate or severe trails until you can tolerate a couple of hours on mild trails.

Second Attempt

Undeterred by her experience at Blackall, Jessie set her sights on another 50k race in Noosa 6 months later.

We wouldn’t make the same mistake twice.

This time, Jessie hit severe trails for all of her long runs. She made the time to make it work, despite the inconvenience of having to get away to the more mountainy trails on Saturday and Sunday.

As the months passed, Jessie’s IT Band got lots of exposure to severe downhill. It toughened up and became more and more resilient.

By the time the next race came around, it was ready.

Jessie smashed her 50k and finished almost an hour faster than in her previous race. Her IT Band didn’t hurt at all.

Conclusion

The key takeaway here is that you need to know what the Rate of Elevation Change is for the race you’re training for. Then categorize it as mild, moderate or severe. Once you know which category it’s in, find trails like that to train on.

Plan out your weekends and trips to the mountains for the next few months (make sure you get your partner in on the plan if needed). In my experience, not getting enough exposure to elevation change is the number one reason trail runners underperform or get injured.

Don’t let it happen to you!

If you’ve already gotten yourself injured, don’t worry. You can get the injured area to calm down and gradually build up the resilience using exposure to downhill on the right kind of trails. If you’d like some help to design and execute on a specific plan to do this, we’d love to help.

Just click the button below to book a free call.