“How can it be physically possible to do this twice!?” My legs just aren’t lifting any more. I’m not out of breath really; I just can’t seem to move. My running has been glorified walking for the last 20 minutes and I am about to lay down on the tarmac. I do so and it takes me 30 minutes to get up. “That was only 21k, how on earth could anyone do that twice?” I don’t get it. But they do, and I know it. It’s bouncing around in my head now. I know full well that every year millions of humans just like me will run a marathon. Many can run further than that and some can run a lot further. I know it’s true. I just don’t get it.

That was the second time I had ran 21k. I’d taken up running a year prior when the idea of running a marathon had captured my imagination. At that moment though, running a marathon seemed about as possible to me as flying. I did it though (eventually). I ran 42.2km without stopping and I actually felt pretty good afterwards. How the hell did that happen?

Well, without knowing it, I used my training to build an aerobic engine capable of running 42.2km. Here’s how it works.

Our Aerobic Engine

The aerobic system allows your body to convert fuel into energy to keep you running. It takes the food we put in (fuel) and makes energy out of it. To do this, it requires oxygen.

Developing the aerobic system is like putting a brand new, finely tuned engine in your car. It will go faster for less energy and it will last longer. The size and power of our “aerobic engine” is what is most important in determining how far we can run and how fast we can do it.

The aerobic system supplies >89% of the energy when you run anything longer than about 1.5km (Gastin et al. (2001). The anaerobic system will supply the rest. So if you want to run further, or if you want to be faster over a long distance, you will need to have the biggest, most powerful aerobic engine you can get your hands on.

How do I get a big powerful aerobic engine?

Long-slow runs are the most effective way to build a big powerful aerobic engine. Your aerobic engine lives in your muscles. It has three components and if you improve any of them the aerobic engine becomes bigger and more powerful. The three components of the aerobic engine are Mitochondria, Capillaries and Myoglobin.

- Mitochondria are little powerhouses that live in your muscle cells. They convert the fuel into energy for your muscles to use. They use oxygen to do this. Long-slow runs increase the size and number of mitochondria.

- Capillaries are tiny blood vessels networked into your muscles. They bring the oxygen and fuel to the mitochondria. Long-slow runs increase the amount of capillaries in your muscles so you can get more fuel and oxygen to them.

- Myoglobin have emergency stores of oxygen. When you are low on oxygen the myoglobin will help out by opening the emergency stores. Long-slow runs increase the amount of myoglobin in your muscles.

When you run at about 50-75% of your capacity you will develop those three features of the aerobic engine most efficiently. When you do that for a long time, you will really cash in. That’s why the long-slow run is the best way to build a big powerful aerobic engine and why it is an essential component of any runner’s training.

So, the next question is, how do you know what pace 50-75% of your “capacity” is?

Determining your slow pace

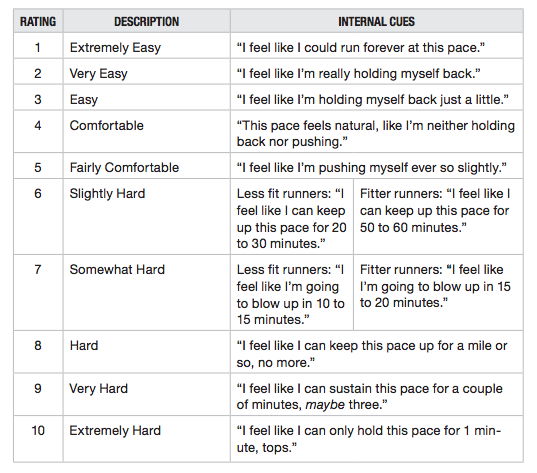

Look up your average pace for your last long run. Start running at that pace and after about five minutes ask yourself which of the following phrases best describes how hard you are working:

Most people will choose phrase number 5 or 6. That means they are doing their long run at 5-6 out of 10 on the rate of perceived exertion or RPE scale. The problem is that 50-75% of our capacity actually corresponds to about 1-4 on the RPE scale.

Our long-slow runs should be about 1-4 on the RPE scale.

So, reduce your pace a little and run for another five minutes. Then ask yourself which phrase best describes how you feel. If you still score above a four, slow down again. Once you feel like “This pace feels natural, like I’m neither holding back nor pushing” make a note of the pace. That should be your “easy-pace” or long-run pace.

Wait! Don’t stop reading yet!

If you do this test then you may well discover that “This pace feels natural, like I’m neither holding back nor pushing” at your current long-run pace. Do me a favour and start running at that same pace again. Now try closing your mouth, and keeping your mouth closed as you continue to run at this pace.

You should be able to continue fairly comfortably for as long as your long runs normally go. It may feel awkward but it should be very possible. I do this with my clients quite a lot and they usually last about 60 seconds before opening their mouth and gasping for air.

If you can’t run with your mouth closed you are running too fast.

Here’s another test. Continue running at this pace and give someone a call on your phone. Talk for a minute and then ask them if they can tell you are exercising.

If they can tell you are exercising you are running too fast.

Ok, here’s another one. Start singing.

If you can’t sing without breaking for air you are running too fast.

So what is going on here?

RPE Miscalibration

The problem is that most recreational runners actually have no idea what running easy feels like because they have never done it. So when they feel like “I’m really holding myself back” they are actually just at a “natural pace, neither holding back nor pushing”.

I call this “RPE Miscalibration”. It happens because as recreational runners we actually have a very narrow window between walking at RPE 1 and running at RPE 4. Elite runners have a much bigger window here. They can run faster for less effort because they are so well trained.

So what should I do?

First off, try the test above and rate your RPE at your typical long-run pace. Make a note of the pace. Then try one of the three tests I mentioned:

- Closing your mouth

- Talking on the phone

- Singing

Slow down until you can complete the test indefinitely i.e. you can run with your mouth closed for a very long time. Then make a note of this pace. This is your new easy-pace.

Now, run all of your runs at this easy-pace pace for two weeks. This “pace-cleanse” is a bit like a “juice-cleanse” and it’s an idea I got from Matt Fitzgerald’s excellent book 80/20 Running. Doing only this easy-pace for two weeks will help you “recalibrate” your RPE. After two weeks you can just use this pace for your long-runs and easy/recovery runs.

At this pace you will maximize the development of your aerobic engine. Once you have a big powerful aerobic engine, there’s no telling how long or how fast you will be able to go.

Check Out My Facebook Live Video!

Every Sunday I’ll be following up my blog posts with Facebook Live videos discussing the subjects in my blogs. Join the conversation!

Recommended Reading

For a little bit more information on the benefits of slow running you should check out these excellent articles.

How Fast Should Your Easy Runs Be? by Jeff Gaudette

Train at the Right Intensity Ratio by Matt Fitzgerald

How Running 80% Easy Could Make You 23% Faster by John Davis