Try This

Grab something heavy from around the house. Something like a drill or a full bottle of bleach. If you have dumbbells, grab one of those. Gently rest the weight on your foot. You should feel fine, right? No pain in your foot, no injury. Now, pick up the weight and drop it on your foot. Better yet, stand up tall, hoist the weight in the air and smash it down on your foot as hard as you can.

I doubt very much that anyone will complete the second part of this test. Why? Well, you would probably break your foot. We can use this little example to help us understand running injuries and how to avoid/rehabilitate them.

High School Physics

In this example, the weight of the object is actually a “mass” (now, we are going to attempt some Physics here – definitely not my strong point so let me know in the comments if I mess anything up). Say the object you used was a drill. The drill is the mass and when we gently place the mass on our foot there is no problem. However, if we throw the mass at our foot then our running season will be cut drastically short. The reason why is that we have added “acceleration” to the mix. If I remember my high school Physics, a chap named Isaac Newton got famous by telling us that “Force = Mass x Acceleration” or…

“F = ma”

So if the drill placed on our foot causes us no problems, but thrown at our foot causes us an injury, it would be fair to say that the Force is the problem. Right?

Now we know that increasing the force makes injury more likely. So how do we relate this to running and why do we care?

Well, when we are walking, our speed is very low, which means the forces are relatively low. This means that our tissues (muscles, tendons, bones) have to withstand less force and are less likely to get injured. Now, if we start to jog slowly, the speed increases a little and so do the forces. Now our tissues need to be a little stronger and more resilient to withstand the forces and avoid injury. If we start to sprint, the forces get really high, and now our tissues need to be really strong to withstand the forces.

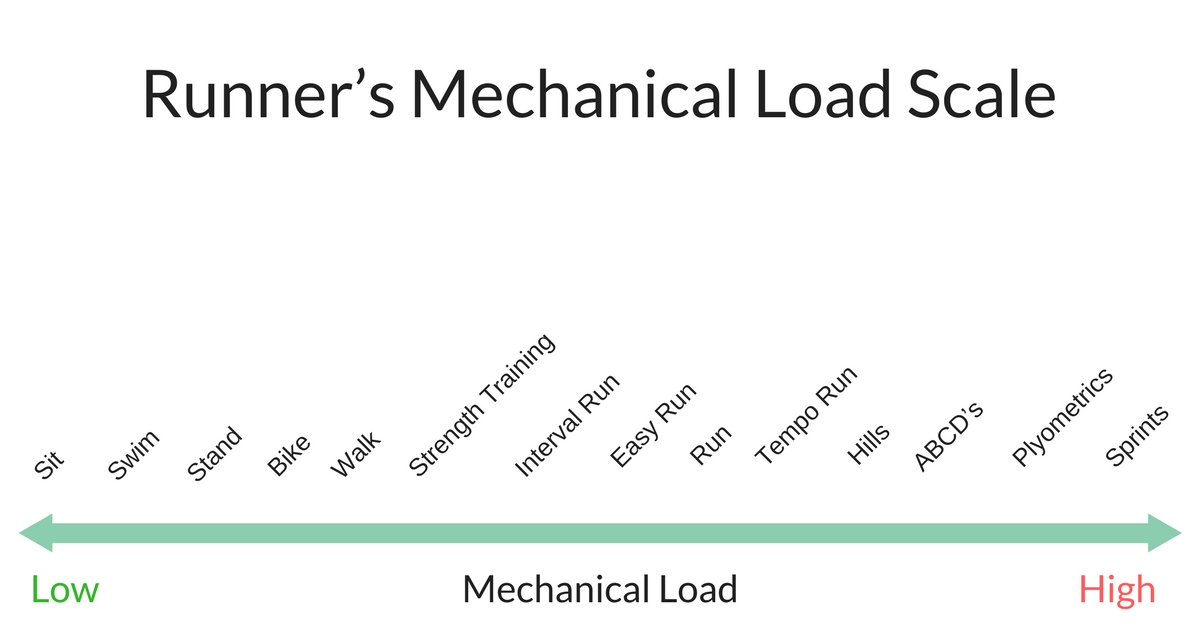

Runner’s Mechanical Load Scale

I’ve translated this information into a Runner’s Mechanical Load Scale. It’s an adaptation of the wonderful Mechanical Stress Quantification pdf from The Running Clinic (which I recommend that every runner print out and put on their fridge). Here’s my Runner’s Mechanical Load Scale:

How can we use this information?. Well, first off, it depends what your situation is: injured or uninjured. First we’ll talk about how this is relevant for runners who are currently injured and then how we can use it to help us avoid injury.

Injured Runners

When working with injured runners, I divide their rehabilitation into 3 phases:

- Protection

- Rehabilitation

- Performance

Those in the Protection Phase have an injury that is easy to annoy or “irritable”. I think of this injury stage like a stressed out Mom. When one of the kids throws a toy and it hits her in the leg, she loses it and screams at the kid. She’s irritable. If a runner had “irritable” knee pain then it would hurt for maybe one single day if they went for a 10 minute run. Or they would limp for a few steps after walking downstairs. When runners come to see me in a situation like this, I consider the injury in the Protection Phase.

To stick with the knee pain example, when you are in the Protection Phase you want to keep the forces very low. So if you stay at the far left of the scale, you can do some walking and swimming and maybe some cycling if it doesn’t hurt too much. After a couple of weeks the knee is calming down and it’s not so irritable. Now you can move into the Rehabilitation Phase.

In the Rehabilitation Phase the injury is not so easy to annoy. Now the knee pain doesn’t really hurt during normal daily life and you can even run a little and not feel it. In the Rehabilitation Phase we want to gradually introduce the forces to the knee and ask the tissues to adapt – i.e. become stronger and more resilient. So we can move a little further up the Runner’s Mechanical Load Scale and try some strength training like squats, lunges and deadlifts. We can also gradually start to introduce some slow running again using something like the Couch to 5K or Running Clinic Interval programs. As we gradually increase the forces on the knee, the tissues adapt to become more resilient. Then they can tolerate a little more force. After a few weeks we can increase the forces even more and move into the Performance Phase.

In the Performance Phase the injury is still restricting your training but it does not come on with easier workouts. Now we want to move up the Runner’s Mechanical Load Scale and introduce some Tempo Runs and Plyometric drills. If we introduce these workouts slowly and in the right volume, the knee will adapt to the forces and become stronger and more resilient still. Eventually you will be able to train all workouts without pain. Now you can consider yourself an Uninjured Runner.

Uninjured Runners

For the uninjured runner, the forces scale can be used to make your tissues as strong and resilient as possible in order to help you avoid injuries. Have a look at your training program and ask yourself if you have been including any work at the far right of the scale. Some sprint sessions or plyometrics. Plyometrics could be exercises like box jumps, lunge switches, squat jumps, burpees, bounding, ABCDs or kettlebell swings. Including a plyometric exercise routine or some hard sprint sessions once a week would go a long way to strengthening your tissues to help them withstand the forces associated with running.

You can also consider forces when thinking about your running technique. If you are a heavy, thudding type runner then the forces will be higher than if you breeze lightly by, running like a light-footed ninja. I’ve written more about how to reduce your injury risk by working on Running Technique here.

In Conclusion

If you are an injured runner, consider the Runner’s Mechanical Force scale as a tool to help you navigate your rehabilitation and structure your exercise routine / running workouts according to where you currently sit in the three phases of rehabilitation (Protection – Rehabilitation – Performance). If you an uninjured runner, be sure to include some training each week at the far right of the Runner’s Mechanical Load Scale. This will help you increase the strength and resilience of your tissues so you can avoid future injuries.

Have you noticed that your niggles get worse with workouts at the far right of the scale? Have you been struggling to figure out why some workouts hurt more than others? Let us know in the comments.

Check out our Facebook Live video!