Have you ever tried to tie your laces with gloves on? It’s pretty difficult right? Even if the gloves are really thin. So what’s that about? Well, with the gloves on we can’t feel the subtle movements of the laces as they brush over the skin on our fingers. The tiny pressures the laces exert on our fingertips are dampened by the layer of material from which the gloves are made. We tie the laces with bigger, more clumsy movements. An approximation of what we can do without the gloves.

Any layer of material between our hands and our environment reduces the richness of the sensation we experience through our hands. It’s exactly the same with our feet. Any layer, no matter how thin, that you place between the skin on your feet and the ground will dampen the sensory experience. Your movements will change, become bigger, more clumsy, less subtle and deliberate.

The Sensory Homunculus

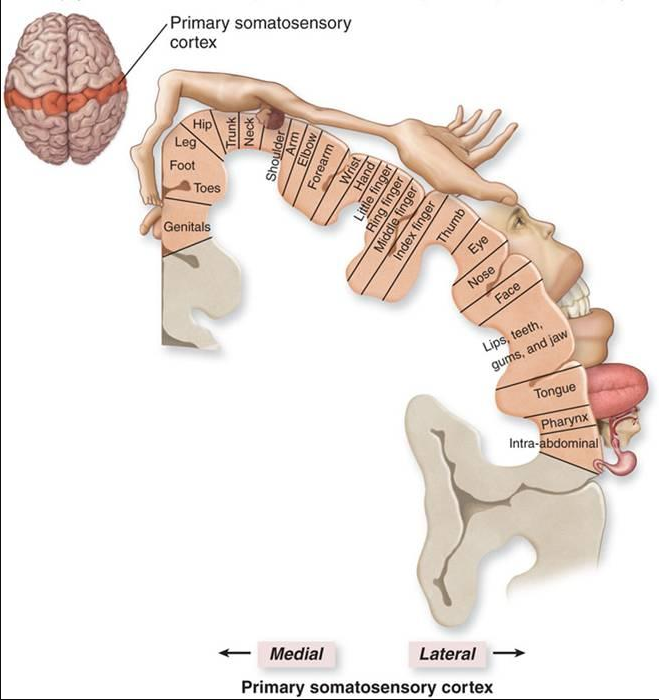

Over time, encasing your feet in lots of layers will actually alter your brain. When you reduce the richness of the sensory stimuli applied to an area of the body the representation of that are in the cortex of the brain will shrink. Our brain has an area of its cortex (surface) devoted to sensation of each part of the body. It’s called the somatosensory cortex and it’s a little sliver down the middle of the brain.

Each part of the body takes up an area of the somatosensory cortex. How big the chunk is depends on how much sensory information the brain receives from that part of the body. So, the chunks of cortex for our lips, eyes and hands are very large. Conversely, the chunks of cortex devoted to the torso, arms and legs are fairly small.

Changing Your Homunculus

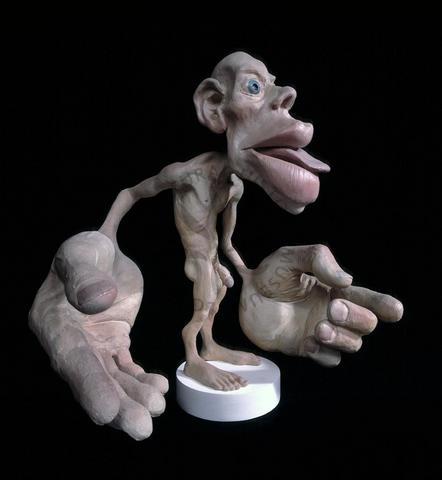

This means the brain “sees” us quite differently from how we are. If you create a model of a human based on how much space each body part takes up in the somatosensory cortex you get an idea of how the brain “sees” us. We call that representation the Sensory Homunculus.

Pretty freaky eh? So that weird looking fella in the picture is how your brain sees you.

The really interesting part is that how your brain sees you changes over time. In people who play string instruments for example, the left hand has a bigger representation in the brain (Elbert 1995). So, in effect, the homunculus of a violinist will have a big left hand. A musician will have bigger ears on their homunculus (Pantev 1998).

It works the other way too. When someone loses a hand, the representation of that hand in the brain will shrink (Elbert 1997). We can deduce from these findings that reduced sensory information will shrink the representation of that body part in the brain and increased sensory information will increase the size of the representation. Or, to put it more simply, if you get a lot of sensation from your feet, then your brain’s sensory homunculus will have bigger feet. If you get less sensory information from your feet, your brain’s sensory homunculus will have smaller feet.

What does all of this mean for runners?

Well, when your brain’s sensory homunculus has smaller feet you will feel less and thus be working with less information. Your decisions about how to land, transfer your weight and push off will be based on incomplete information. It’s like you’re about to go into battle and someone spilled their coffee on the terrain map.

This usually culminates in runners adopting a technique that is a little different from how it would be if they only ran in their bare feet. The most important and most common technique errors are low cadence and high impact forces. These are often linked. High impact forces means that you are “noisy” or “heavy” when you run. It means you hit the ground too hard when you run and in the research that is referred to as a high Vertical Loading Rate (VLR). A high VLR, aka being a heavy runner, has been linked to increased injury risk (Davis 2015).

Try this at home

Put your running shoes on and run on a treadmill or just around your living room. Now, take your shoes and socks off and do it again. Did you notice anything different about the way you run? I’d say >90% of runners will feel some change in the way they run once they are in their barefeet. What you have done here is give the brain more information from your feet. Based on that information the brain has made some different decisions about how to move.

Your brain is changing your running technique to reduce the impact forces. As discussed above, higher impact forces are associated with higher injury risk. When you remove the layers of material between the skin of your feet and the ground your brain will improve your Load Absorption Strategies.

Should I always run Barefoot?

Well, that’s a good question. If you can be very patient you could learn to run in completely bare feet all the time. It would likely take quite a few years for your muscles, tendons, bones and skin to adapt and allow you to run a significant volume in bare feet. If you want to do that though, go for it (actually, if you live here in Ottawa, don’t do that in the winter unless you want to lose your toes).

It’s unlikely that many people reading this blog will be interested in making this extremely slow transition to a completely barefoot runner. I know I don’t really intend on doing it any time soon. So, the question is, can we learn to adopt some of those load absorption strategies that the brain adopts in bare feet even when we have our shoes and socks on?

Using Barefoot Running to Improve your Running Technique

A strategy I often use with runners is to have them do some running in completely bare feet on a regular basis. After a while we start to see their running technique in shoes look more like their running technique in bare feet. It kind of “creeps” into their regular running form. They start to run softer, with a higher cadence and less overstriding.

I’ve found the best way to structure this is a “barefoot day”. The barefoot day is one day a week when you run in your bare feet. It’s a good idea to put the barefoot day on the same day as a steady/easy/recovery run. Or you could put it on your strength training day.

So say we’ve picked Saturday as our barefoot day. We don’t want to do too much too soon. Our feet aren’t used to this so let’s take it easy. On the first barefoot day, you’re just going to do 1 minute in your bare feet. You can do it on a treadmill at the gym or outside if it’s warm enough. If you go outside you can run on almost any surface including concrete. You won’t be able to run on ground with lots of pebbles, stones or gravel. Only do 1 minute for the first barefoot day though. If you have put the barefoot day on the same day as an easy run, go put your shoes on after the 1 minute barefoot and then finish your run.

The following Saturday will be barefoot day 2 and you will do 2 minutes. A week later on barefoot day 3 you will do 3 minutes. On barefoot day 4, do 4 minutes. Continue this progression adding 1 minute per week. You can continue this for as long as you like but at some point the run will be “long enough”. So, if you get to 30 minutes barefoot and you decide that’s enough, just stick with that. Now you have a 30 minute run on barefoot day. Your technique during your other runs will start to improve naturally as the load absorption strategies you are learning during your barefoot runs start to creep into your regular runs.

If you decide to do the barefoot day on the same day as an easy run you could gradually make the easy run a barefoot run. Say you normally do a 40 minute easy run on a Saturday. Each time you add a minute to your barefoot run you subtract one from your easy run. Week 1 is 39 minutes easy (in shoes) and 1 minute barefoot. Week 2 is 38 minutes easy (in shoes) and 2 minutes barefoot. Then you just continue this until the barefoot run “absorbs” the east run. It’s important to keep the intensity the same though. Your barefoot runs should always be at an easy pace to keep the mechanical load similar.

When to Plateau

At some point, as you increase the duration of the barefoot run week by week, something will start to grumble. Usually your calves, feet or shins. They are working harder now. They are helping to absorb the impact forces instead of getting a free ride and leaving it all up to the knees and hips. This is a good thing. We have to give them time to adapt though so when you start to feel discomfort either during or after your barefoot runs it’s time to plateau.

Say you get to 20 minutes duration for your barefoot run. Then your feet are starting to hurt a bit after the run. You’re going to keep the duration of the barefoot run to 20 minutes for the next few weeks. That’s called a plateau and it will give the tissues time to adapt. Once you notice the discomfort is no longer coming on, you can add another minute the following week and each week thereafter. If at say 25 minutes the same or another discomfort comes on, then you’re going to plateau again until it goes away. You’ll stay at 25 minutes now for a few weeks and then start increasing when your legs feel ready.

Should I change my shoes?

If you’re going to use the barefoot day strategy to work on your technique then I wouldn’t recommend changing your shoes at the same time unless you have been advised to by a competent professional. The reason is that you are changing too much at once and you’re likely to run into trouble. That being said, if you start to really enjoy the barefoot runs and want to move to a more minimal shoe then I certainly think it’s worth considering.

What I’d recommend in this case is to wait until your barefoot run is at least 30 minutes and then continue at 30 minutes each barefoot day for 6 weeks. That should give your tissues time to adapt. Now, continue the barefoot day as you have been at 30 minutes and start to transition to more minimalist shoes. To help you do this without getting injured, check out my blog How to Transition to Minimalist Running Shoes Without Getting Injured.

So, what do you think? Are you going to give the barefoot day a try?