Tendonitis in runners is an extremely stubborn problem. It is usually experienced as focul (small area) pain within the tendon itself. The Achilles, patellar, hamstring and gluteal tendons are those most commonly affected among runners. The pain usually comes on immediately with running but then warms up and can often go away during the run. The pain is often worse first thing in the morning.

In part one of this series we talked about the pathology (disease process) underlying tendonitis. In this article we are going to discuss the history of tendonitis treatment, how it has developed over the last 20 years and where the research currently stands.

Chapter One – The Inflammation Theory

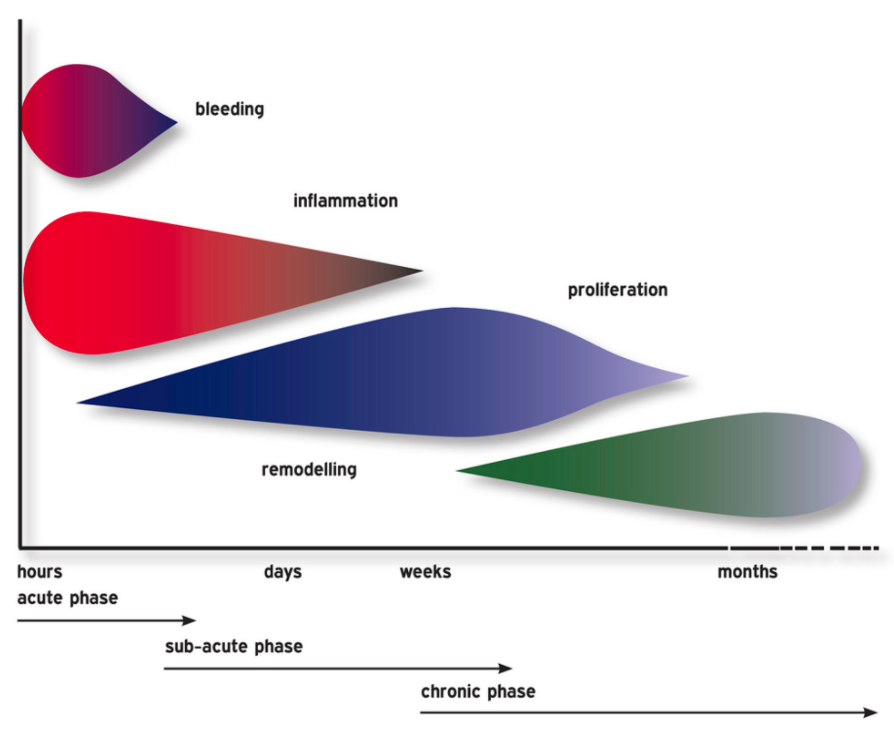

Up until about the 1990’s it was believed that painful tendons were ‘inflamed’. Inflammation is a reaction of the body’s tissues to harmful stimuli. Inflammation is the first stage in the body’s normal 3 step healing approach: Inflammation, Proliferation, Remodelling.

The three stages of healing usually go pretty well. Most of us have sprained our ankle at some point. You get a big nasty inflammation at first and it hurts to walk on it. After a couple of weeks the inflammation is starting to resolve and walking is okay. Leave it be a few more weeks or a couple of months and you can get back to running. Healed.

Before the 1990’s it was believed that tendonitis was a case of acutely overloading the tendon and causing an inflammation. This led to the term ‘tendonitis’ because the suffix ‘itis’ means inflammation in latin. It was expected that the tendon was just in the first stage of healing. Leave it be few a few weeks/months and the tendon will heal itself.

For this reason, most of the medical advice and treatment at this time centred around the usual strategies to resolve inflammation. These were primarily the RICE protocol of rest, ice, compression and elevation – questionable interventions at the best of times (van den Bekerom 2012).

Unfortunately, none of this stuff seemed to help much.

Chapter Two – The Painful Eccentrics Theory

This is where our story takes an interesting turn. Back in the mid 90’s a young doctor by the name of Håkan Alfredson was having some trouble with his Achilles tendon. He tried the strategies mentioned above that focussed on resolution of the ‘inflammation’ but did not see any improvement. He discussed the problem with some of his surgeon colleagues as he wanted them to operate on him (I’m not sure what type of operation he wanted). Alas, his surgeon friends did not think the problem was bad enough to operate on, so they refused.

Frustrated, Dr Alfredson figured he could convince his pals to operate if he just made his tendon worse! Since, in his mind, the tendon was inflamed by overloading, he just had to load it up some more and make it worse. So he threw on a backpack filled with weights and started doing heel drops until his tendon screamed for mercy. He would do almost a hundred painful heel drops a day!

He focussed his efforts on the eccentric part of the movement. Eccentric refers to the lowering part of the movement when the muscle is lengthening. So if you imagine standing on your tip toes and then lowering down to the ground slowly then your calf muscle is lowering you down eccentrically. The opposing type of muscle action is concentric. Concentric is the raising part of the movement when the muscle is shortening. When a muscle is static but contracting it is known a an isometric contraction. So if you are standing still and then raise up to stand on your tiptoes the calf acts concentrically to lift you up. If you stay up on your tiptoes the calf muscle acts isometrically to keep you up. As you lower down to the ground the calf muscle acts eccentrically to lower you down slowly.

Alfredson focussed on the eccentric (lowering) part of the movement (I’m not sure why). Since he was trying to make the problem worse, he was adding more weight if it didn’t hurt. The funny thing is, as the weeks passed he had to keep adding more and more weight to make it hurt. After a while it wasn’t hurting as much on a day to day basis. So he kept it up and after a few months he didn’t have any pain anymore! Weird eh?!

The really cool part here is that he started doing research on this painful eccentric loading. His research subjects actually got better too! He somehow managed to convince people to do this brutal program of heel drops:

- 3 sets of 15 reps twice a day with a bent leg and a straight leg (that’s 180 per day!)

- It must hurt, if it doesn’t, add more weight you big wimp

People got better! This was the first major breakthrough in tendonitis treatment. Dr Alfredson would go on to have a distinguished career in tendonitis research and treatment. He would later establish the Alfredson Tendon Clinic in Sweden.

Here’s the man himself sharing his story with Pure Sports Medicine…

Chapter Three – The Continuum Model

Alfredson’s discovery led to a ton of research on tendon loading. It became apparent that whatever was going on with tendonitis wasn’t the typical inflammation that constitutes the first stage of the normal tissue healing response. For this reason the term ‘tendonitis’ was replaced with the term ‘tendinopathy’ – meaning ‘tendon disorder or disease’.

Lots of smart people did lots of studies to try and figure out what is happening in tendinopathy. In 2009 a group of researchers from Australia published a paper on the ‘Continuum Model’ of tendon pathology (Cook 2009). They proposed that tendon degeneration (breakdown) would occur along a three stage continuum if the tendon is chronically overloaded. This seemed to catch on in the medical community and forms a big part of our current understanding of tendon pathology.

Rather than being an acute inflammatory-type injury that could be ‘rested away’ like an ankle sprain, tendinopathy is more of a chronic problem. The structure of the tendon gradually changes in response to chronic overloading. These structural changes leave the tendon incapable to tolerate the loads placed upon it and pain ensues. I talk a lot more about this model in part one of this series on tendonopathy.

Chapter Four – The Loading Theory

More and more research was done on different aspects of the tendinopathy problem. Some looked at the basic science (cellular changes in the tendon). However, many studies zoomed out to more practical questions like “What’s the best way to treat tendinopathy?”. Many studies started to look at other protocols that ‘loaded’ the tendon.

Eccentric loading had become the mainstay of treatment for tendinopathy and I personally remember giving clients eccentric heel drops for Achilles tendinopathy back in the day. I would have them come up on their tiptoes on two legs and down on one and use a backpack to add weight. I even remember giving one poor lady that brutal 180 heel drops a day Alfredson protocol I mentioned above and she did it! When she came back a few days later complaining that her calves were so sore she could hardly walk, I asked her if her Achilles hurt when she did the exercise. When she told me that the calves hurt but not the Achilles I got her to add more weight! (I had read the protocol in a textbook after all). She didn’t come back to see me again.

Meanwhile, smarter people than me were investigating whether it was really important that the exercises were painful and whether we need to focus only on the eccentric part of the exercise. Other protocols were tested that didn’t require the subjects to feel pain during the exercise. They also were a little more practical in that some had people do loading exercises 3 times a week instead of twice a day.

In a review in the British Journal of Sports Medicine in 2009 a group of researchers analysed all of the studies done on tendon loading to date. They comprised lots of different loading protocols (not just those focussed on eccentrics). They reviewed 32 studies in all and concluded:

“There is little clinical or mechanistic evidence for isolating the eccentric component…Clinicians should consider eccentric-concentric loading alongside or instead of eccentric loading in Achilles and patellar tendinopathy.” (Malliares 2009)

Put more simply, they were saying that loading works whether it is concentric, eccentric or both.

Things are looking better at this stage. We understand that the tendon problem is not inflammation in the typical sense and resting probably won’t resolve the issue. We also have quite a bit of evidence that loading the tendon is an effective way of treating tendinopathy.

Chapter Five – Isometrics for Tendon Pain Relief

In 2015 an Australian Physiotherapist names Ebonie Rio published a small study looking at the use of isometrics (static contractions) for pain relief (Rio 2015). In her clinical work, she had found that doing a few sets of isometric holds would cause an immediate (but temporary) reduction in tendon pain. She believed that this would be useful for athletes ‘in-season’ as a method to help reduce pain for sporting events. Kind of like taking a painkiller.

In the study she had 6 athletes with patellar tendinopathy (the tendon under the kneecap) do a kind of single leg squat and then rate their pain. She then had them do 5 x 45” isometric hold on a knee extension machine (the machine where you sit down and straighten your knee into resistance – she had them hold it still against a heavy weight at 60° for 45 seconds). She found that their pain during the single leg squat test dropped from about 7/10 to 1/10. The effects lasted at least 45 minutes. Pretty good eh?

She also had the same people rate pain on the test before and after doing a bunch of resisted knee extensions (isotonic – knee is bending and straightening against resistance). Doing that only dropped their pain from about 6/10 to 4/10 and the effects did not last to 45 minutes.

Now, this is only one small study, so we don’t want to get carried away. In 2019 the effectiveness of isometrics to immediately reduce tendon pain has been seriously called in to question. That is principally due to the fact that researchers have ahd trouble replicating these findings (Silbernagel 2019). However, trying isometrics to see if they help with pain seems to be a relatively harmless intervention. Here’s how I use it in the clinic:

- Run on a treadmill (or do another test that provokes the pain)

- Rate the pain on a 1-10 scale

- Do 5×45” isometric holds (pushing with about a 7/10 effort into something that won’t move)

- Run on a treadmill (or do the same painful test as at the beginning)

- Rate the pain on a 1-10 scale

- If your pain improves significantly then do the 5×45” isometrics before every run

The type of isometric exercise would depend on where you have your tendon pain. For Achilles tendinopathy for example, you would use a single leg calf raise and hold at the top while pushing a wall. For the patellar tendon, you could lean back on a wall while squatting and push into the wall. I’ll talk more about the specifics of these when I dig into the specific treatment of different kinds of tendinopathy later in this series.

Chapter Six – Tendon Neuroplastic Training

In 2016 Ebonie Rio and her colleagues were back at it. This time they published a paper proposing a method to take the principles learned from the loading research mentioned above and improve on it. To this point we have seen significant progress in tendinopathy treatment. However, it is still a very difficult problem. Not everyone gets better and recurrence rates are high. Rio and her colleagues wondered if one of the reasons for this are changes in motor (movement) control within the nervous system (brain and nerves) that occur as the result of tendinopathy (Rio 2016).

The theory goes that the tendinopathy causes changes in motor control within the nervous system. These changes persist for a long time, even if the tendinopathy itself improves with loading rehabilitation. These changes in motor control might lead to altered recruitment of the muscle and tendon complex during movement tasks (like running) in the future. These changes in muscle and tendon recruitment patterns might lead to overloading in the future. Doing your loading exercises with external pacing might help address this problem.

I know, that’s a lot of ‘might’s’. However, this is the cutting edge of tendinopathy research. Researchers are now trying to reconcile cellular changes in the tendon tissue with changes in the nervous system and how this all relates to loading.

In her 2016 paper Rio and her friends proposed using a metronome to make the loading exercises more cognitively demanding. The idea being that trying to match some form of external pacing will make the task of strength training more skillful. This may increase excitability and decrease inhibition to the involved muscles and tendons by the nervous system.

This all sounds a bit complicated, but in practice it is very simple. Say you are going to do calf raises to load your Achilles tendon to treat your tendinopathy. All you need to do is set a metronome to 20 beats per minute. Then match the beat so you reach the top of the calf raise on one beep and the bottom of the calf raise on the next. In theory this will make the task more skillful and may help address some of those changes in the nervous system that we talked about above.

Chapter Seven – Putting it all together

So, now that we understand a brief history of tendinopathy treatment, how are we going to put it all together? The last 20 years of tendon research has told us a lot. We know that the tendon is not inflamed in the typical sense and that resting probably won’t help that much. We also know that heavy loading seems to help rehabilitate tendinopathy and that we don’t need to just do the eccentric (lowering) part. We think that isometric exercises might help as a kind of painkiller and we also wonder if external pacing for our loading exercises might be a good idea.

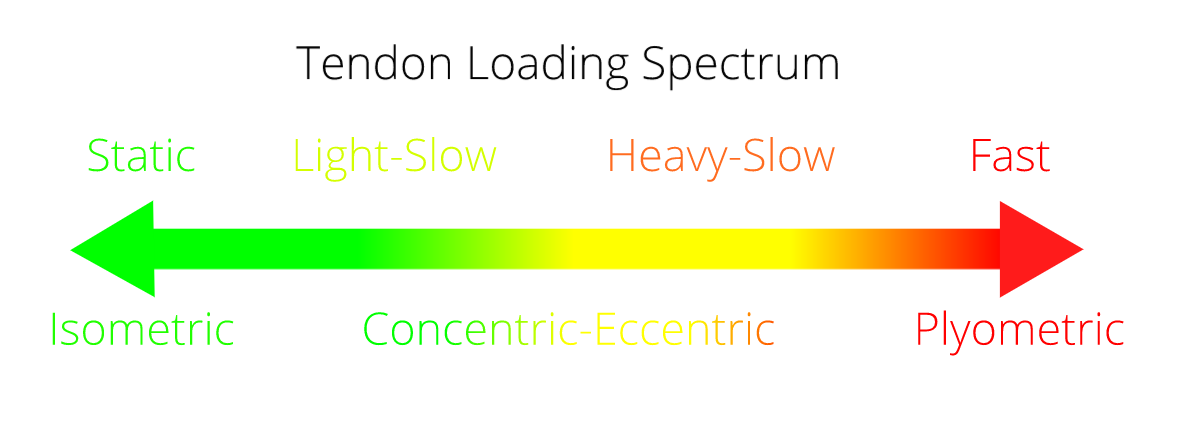

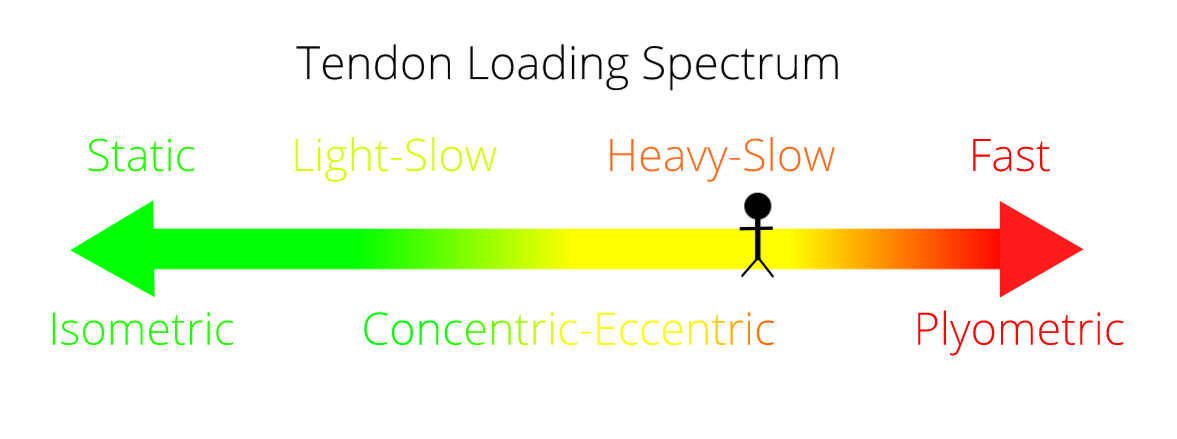

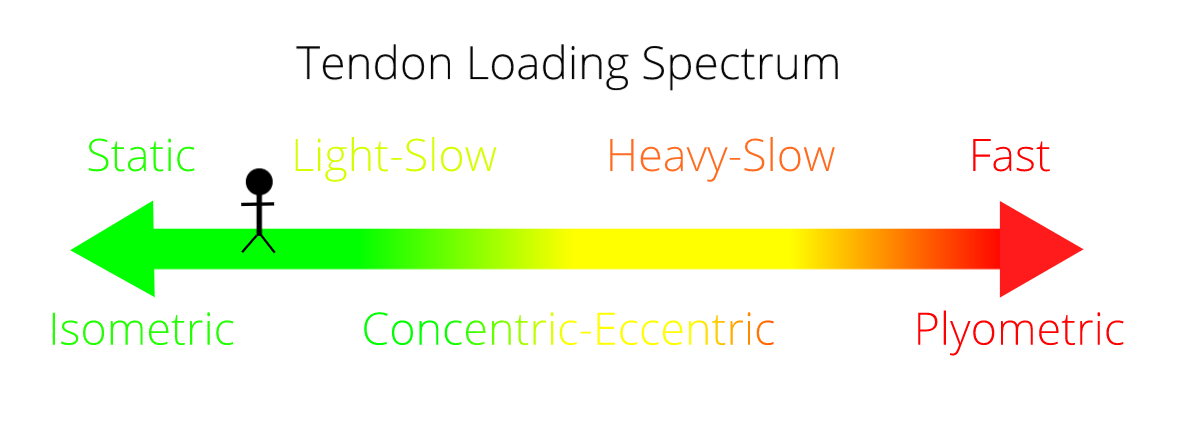

In the clinic, I put this all together in what I call the Tendon Loading Spectrum. Basically we go from very low tendon load on the left to very high tendon load on the right.

When someone comes in with an Achilles tendinopathy, I ask myself where on the spectrum they currently sit. That is to say, what intensity of loading can the tendon handle? If someone has tendon pain with running but not walking, then the tendon can probably tolerate heavy-slow loads but not fast. We would work on heavy calf raises to strengthen the tendon and use a metronome set to 20 beats per minute to dictate the speed of the calf raises.

Now, say someone else comes in with Achilles tendinopathy but they say to me that it hurts when they walk. I would say the tendon can tolerate static loads but not light-slow. So we would work on isometric (static) calf raises to try and get the pain down.

The goal of rehabilitation for tendinopathy therefore is to work out where on the Tendon Loading Spectrum you currently sit. You then begin your tendon loading at that intensity. You add weights once you can tolerate it and as your tendon starts to feel better you move to the right, further up the Tendon Loading Spectrum. This will take a long time. Most of the research protocols I have referred to in this article took place over 3-6 months. That is because tendons are very slow to adapt. So you will have to be committed and patient if you intend to fully rehabilitate your tendinopathy.

Your activities would follow along as guided by your symptoms. Walking, running and sprinting are encouraged once the tendon can tolerate those loads, but not before. That means if your tendon hurts for 2 days after a 5k run it is obviously not able to tolerate a 5k run and you will have to run less. However, if the 5k run provokes no reaction in the tendon after you finish the run then you should continue to run 5k (or a bit more) regularly to help strengthen the tendon.

Summary

Now we have a pretty good picture of how tendinopathy treatment has evolved over the years and where it currently stands. We started with some pretty useless strategies to treat ‘inflammation’ based around rest. From there we started to see some progress with painful-eccentric loading in the 90’s. After that we discovered that we should be loading concentrically and eccentrically (up and down) and that the exercises didn’t need to hurt.

Nowadays we’re trying to integrate the role of the nervous system. We’ve discovered that isometrics might be useful as a kind of painkiller and that external pacing (metronome) might be useful as a way to optimize the effectiveness of the loading exercises.

Now we’re going to talk about exactly how to rehabilitate the different tendon problems. Just click the link that applies to you: