So you’re gearing up for a beautiful summer of running. You’ve got the race calendar all mapped out and you’ve registered for a spring half marathon. Unfortunately you’ve also noticed that your heel pain is getting worse in the morning after a long run. It makes you limp with the first few steps out of bed in the morning now. After reading part one of this series on heel pain when running you’ve confidently identified a nasty case of plantar fasciitis (now known as plantar fasciopathy). Fortunately for you, we’re going to be talking all about treating heel pain from running in this article.

Many runners worry about doing more damage if they continue to run with heel pain. This is mostly because they don’t understand the nature of the problem. The foundation of any successful effort at treating heel pain from running is to understand the pathology. Plantar fasciopathy is the most common cause of heel pain in runners. You need to understand what it is and why you got it before you can start treating it.

If you haven’t yet read part one of this series then go and do that now. Then you’ll understand what you are dealing with. Once you have that foundation, you can use this article to devise your own self-treatment plan. We’re going to dig through your treatment options one by one and review the evidence for them. Then you will be able to make an informed choice regarding your treatment.

Do I have Plantar Fasciopathy?

The first step in this problem is to make sure that you have accurately diagnosed the problem. Do you know how to tell the difference between a plantar fasciopathy and an insertional achilles tendinopathy? If the answer is no then you obviously didn’t go back and read part one! Do that now.

Once you are sure that we’re dealing with a case of plantar fasciopathy we then have to establish whether the problem is acute (short term) or chronic (long term). For most injuries, the cut off between acute and chronic is 3 months. For plantar fasciopathy however, we are going to make the cut off 12 months. The reason being that 90% of cases of plantar fasciopathy will resolve within 12 months regardless of what kind of treatment you receive. In the sports medicine world we call that the Natural History of the disease (pathology).

Treating Heel Pain from Running

The treatments you would consider will be very different if you are one of the unlucky 10% who still has plantar fasciopathy over one year after it first comes on. Here’s how we’re going to break down your treatment options.

| Acute (< 12 months) | Chronic (> 12 months) |

| Natural History | Plantar Fascia Stretching |

| Plantar Fascia Stretching | Plantar Fascia Strengthening |

| Plantar Fascia Strengthening | Running Technique Work |

| Taping | Shockwave |

| Self Massage | Steroid Injection |

| Heel Cups | Surgery |

| Night Splints | |

| Orthotics | |

| Running Shoe Change |

Treating Acute Plantar Fasciopathy

If you’ve had your heel pain less than a year then there is every reason to be optimistic. As I mentioned earlier, 90% of cases will resolve within 12 months. This is called the Natural History of plantar fasciopathy.

Natural History

Since 90% of plantar fasciopathy cases resolve within 12 months regardless of treatment then one option is to just wait it out. If the pain is not that bad and it’s not interfering with your running too much, then this is a completely reasonable option. You will naturally adjust your running habits based on the feedback from the pain. When you do too much it will hurt more, so you will do less next time. If you continue in this vein for 3-12 months we would expect you to make a full recovery and be back to full running capacity within the year.

One problem with this approach is that many runners are far too restricted by the pain to just wait it out. If you normally run 50 km a week but your heel pain only lets you run 20 km, you probably won’t be content to just “wait it out”. The other problem is the 10% of cases that don’t resolve within a year. Unfortunately, we don’t yet know why those people do not recover. It could well be that you wait a year and your symptoms are still there.

Training Load Management

If you have read pretty much any of my articles then you know that Training Load Management is by far the most important intervention for any running injury. Simply put, this is how much you run in a week. When we think about training load we want to consider the intensity of the running as well as the distance or duration.

If your heel pain is so bad that you can’t run at all without limping then unfortunately you need at least a week of rest. However, if you can run for 1 minute, walk a minute and then repeat this 3 times, you may be able to use running to help treat your injury.

To make sure your training load is not overloading your plantar fascia you need to monitor the symptom response to load. This sounds technical but actually it’s very easy. After each run you just have to decide if your plantar fascia tolerated the load that the run placed on it. To do that you will need a litmus test. Your litmus test is just something you can do easily during which you feel the pain in the heel. The easiest one for most people is the first few steps out of bed in the morning.

On a morning when you didn’t run the day before pay attention to the pain in your heel with the first few steps out of bed. Give it a pain score out of ten, this will be your baseline. For example:

“My heel pain was 3/10 with the first few steps out of bed this morning”

Do whatever run you were planning to do today. Let’s say it was a 10k. The following morning you re-do the litmus test to see if the pain score is the same.

“The morning after my 10k run my pain score was 6/10 with the first few steps out of bed”

Since the pain has increased we know that your plantar fascia did not tolerate the load of the 10k. You failed the litmus test and need to reduce either: your speed, your distance or both. The next day you try 5k.

“The morning after my 5k run my pain score was 3/10 with the first few steps out of bed”

Since your pain score did not increase from your baseline of 3/10 then you know the plantar fascia did tolerate the load of the 5k. You passed the litmus test. You know your load tolerance is somewhere between 5 and 10k per run. (An increase of 1 point on the pain scale is not a problem)

Plantar Fascia Stretches

In 2006 a group of researchers from Rochester, NY compared the a ‘plantar fascia specific’ stretch to calf stretches. They found that scores for pain first thing in the morning dropped from 7/10 to 4/10 in the plantar fascia stretch group. The calf stretch group only dropped to 6/10. This suggests a slight superiority of the plantar fascia specific stretch over the traditional calf stretch (DiGiovanni 2006).

For this reason, I include the plantar fascia stretch in the home program for many of my plantar fasciopathy clients. It’s dead easy, just sit in a chair, cross your legs and pull your big toe up to your face. Hold that for 30 seconds and repeat 3 times. Do that once a day.

Plantar Fascia Strengthening

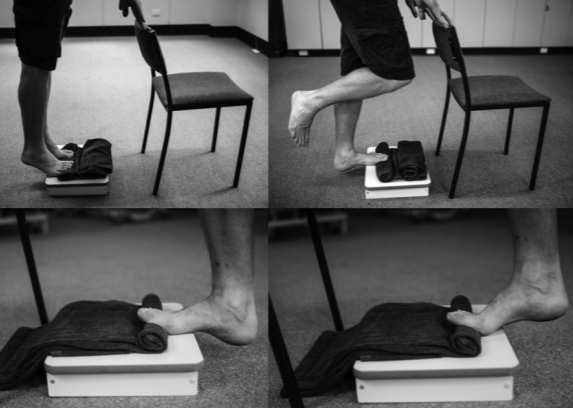

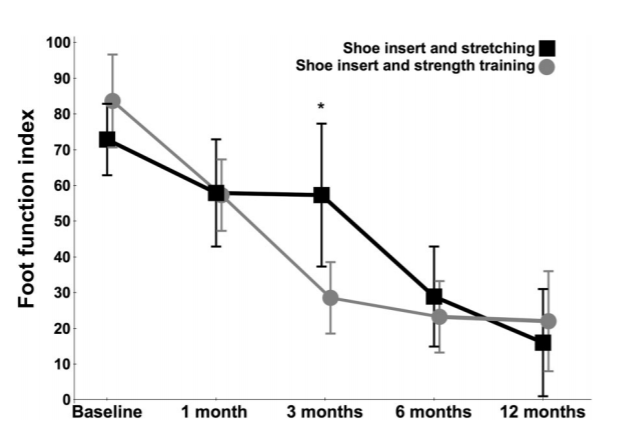

The first real breakthrough in chronic plantar fasciopathy rehabilitation came in 2014 when Rathleff and colleagues published their study on high load strength training (Rathleff 2014). They used a questionnaire called the Foot Function Index to measure how bothersome the heel pain was. They had one group do the plantar fascia stretch described above and had the other group do heavy calf raises with the toes wedged up on a towel.

After 3 months the strength training group had significantly higher scores on that Foot Function Index, although by 6 months the difference had levelled out.

The fact that the differences levelled out might sound a little discouraging but bear in mind that you will be doing the stretching and the strengthening – two interventions with proven effectiveness. Also bear in mind that the people in both these studies had chronic (> 12 months) heel pain. This is a much harder problem to treat than acute (< 12 months).

So in addition to the plantar fascia stretching that you’ll be doing three times a day, I recommend you do some strengthening every other day. The study protocol went something like this:

Every Other Day:

- Weeks 0-2 = 3×12 RM

- Weeks 2-4 = 4×10 RM

- Weeks 4-6 = 5×8 RM

RM means Rep Max which just means the maximum load you can do this amount of reps. So 3×12 RM means 3 sets of 12 reps holding the heaviest dumbbell you can manage. I usually find a 5, 10 or 20 lb dumbbell is plenty for most people at first. You could also wear a backpack stuffed with books or detergent or something if you don’t have weights. You can see a demo video of the exercise below. See how the sets increase and the reps decrease as the weeks pass? That’s because we want you to use heavier weights. So weeks 0-2 you may do 3×12@10lbs but by weeks 4-6 you do 5×8@20lbs. In both cases you are doing Rep Max – the heaviest weight you can manage.

We also want you to go super-slow. In the study they took 3 seconds on the way up, 2 second hold, 3 seconds on the way down. Try it for yourself, this is irritatingly slow. An alternative is to set a metronome to 20 bpm. Then you reach the top on one beep, pause until the next beep, then reach the bottom on the next beep. That’s 3 seconds up, 3 second hold, 3 seconds down.

It’s very important that you do this on a step not just on the floor. You also have to make sure you lower your heel down below the height of the step until you feel a maximum stretch in the calf. We know that reduced ankle flexibility is a risk factor for plantar fasciopathy (see Part I). The authors of this study hypothesised that increasing ankle flexibility by stretching the calf during this exercise may be one of the reasons it works.

An important side note for us runners is that the authors of the study prohibited running for these subjects until they could walk 10km pain-free. Personally, I just use the interval run:walk program mentioned above. For a more detailed description of that process check out this article.

Taping

Taping or ‘strapping’ is often used by Physiotherapists to reduce pain for plantar fasciopathy. Speaking from experience, it works pretty well. I get my client to walk around the clinic and rate their pain from 0 to 10. Then I put the taping on and get them to do it again. They usually score their pain a few points lower and smile as they say, “yeh, that feels a bit better”.

This is very anecdotal, meaning based on experience not robust scientific studies. Unfortunately, ‘robust scientific studies’ on taping are actually pretty similar to my little story above. All the studies look at the immediate effect of taping and none seem to look at the long term effect. Also, they all seem to say the same thing as I did above. Put on the taping and the pain will feel a bit better straight away (Podolsky 2015, Park 2015, Hyland 2006, Landorf 2005).

You probably wont get any long-term benefit from taping. That is to say, you won’t have heel pain for less time overall, but it will probably hurt less when you have the taping on. I recommend it more for people with acute heel pain (<12 months) and teach them how to do it themselves. I usually don’t bother for the chronic (>12 months) because the pain isn’t as bad and it probably won’t make any difference in the long run.

There are a bunch of methods you can use but here’s a video with an example. Use the brown leukotape rather than the white athletic tape (it costs more but it sticks better and it’s stiffer). Walk around and rate your heel pain out of 10, then tape it up and repeat. If it feels better, congratulations, you can use taping as much as you like to help manage your symptoms. You may find you are able to run a bit more with the taping on than without.

Massage and Self-Massage

There’s not really much research I can find on massage for plantar fasciopathy. That’s ironic because I do it with patients all the time! One review of the literature concluded that there is some evidence hands-on treatment (manual therapy) reduces pain in the short-term (Pollack 2018). This conclusion is in-keeping with most research on manual therapy which shows it usually reduces pain temporarily but doesn’t make too much difference in the long run. However, similar to the taping mentioned above, in the short term you may find it helpful to reduce your symptoms.

There is no secret, special way to massage the plantar fascia that has been proven to be any more effective at reducing pain than any other. So please just feel free to get into the sore spots with your thumbs and go to town! Some people like to use a lacrosse ball, a tennis ball, a golf ball or even a frozen bottle of water. Again, this all comes down to preference. Do whichever you like the feel of. If you get up and walk around afterwards and your pain is a bit better, great, do that whenever you feel like it.

Heel Cups

Heel cups are little plastic pads that you put under your heel in your shoe. They are squishy and sometimes have gel in them to offer some shock absorbing effect.

Despite being one of the most common interventions for heel pain, relatively little research has been done into their effectiveness. In research studies they are usually part of the control group. Meaning they are the ‘standard care’ that the new intervention is being compared to.

One study surveyed 411 people with plantar fasciopathy and they ranked heel cups as the least effective treatment when compared to things like steroid injections, painkillers, rest and ice (Lowell 1996). More recently a group looked at prescribing custom-molded heel cups and determined they could be “used as an effective method for the treatment of plantar heel pain”. However, this study had only 16 subjects, no control group and multiple other problems, so we can’t read too much into that conclusion (Li 2018).

I can’t see too much research coming out in the future on heel cups. If they do help it is probably only a little bit. However, they are cheap and if you put them in your shoe and it hurts less to walk immediately, I’d say use them.

Night Splints

Night splints are a soft boot or sock that you wear to bed that will keep your foot pulled up into dorsiflexion. The theory goes that they will improve the flexibility of your calf by stretching it overnight and thereby improve your foot biomechanics. However, only one study I have found actually measured this and they found that calf flexibility didn’t actually change (Wheeler 2017).

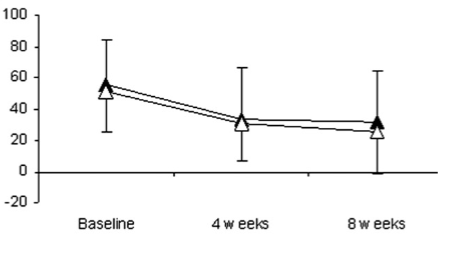

That Wheeler study was probably the best to date on night splints. They had one group do a program of exercises and the other group did the same exercises but also wore the night splint. Unfortunately after 3 months there was no difference between the groups. Both groups pain came down by about 1.5 points though, which is not bad considering the people in the study had had heel pain for an average of 2 years (Wheeler 2017). These results reflected those of an earlier study (Probe 1999).

The other studies on night splints are not quite so robust. However, there does seem to be some short term benefit for those with acute plantar fasciopathy (< 12 months). Lee and colleagues showed pain scores reduced by 3 points after 8 weeks of using the night splint with orthotics (the other group only got orthotics and improved 1 point) (Lee 2012). This study was pretty small though.

In summary, night splints may help a bit if you have had heel pain less than one year.

Running Shoes

“Supportive shoes” or “arch support” is pretty much the first thing recommended to a runner with plantar fasciopathy. Whether by a fellow runner, a physio, a doctor or even their grandma. Supportive shoes are seen as essential in order to prevent and/or treat plantar fasciopathy. In spite of this it’s really hard to find any studies that actually look at supportive shoes as an intervention – i.e. a treatment. In fact, I can’t find any.

Shoes with cushioning and arch support are often frequently mentioned in published scientific journal articles. Shoes that are “too worn” or “unsupportive” are often demonised (Young 2001, Singh 1997). You would think there would be a ton of high quality evidence linking unsupportive shoes to plantar fasciopathy.

Nope.

Not that I can find anyway.

All this to say, the research really can’t guide us much in terms of shoe selection. Will supportive shoes help prevent or treat heel pain? Do minimalist shoes make you more likely to get plantar fasciopathy? Honestly, I just don’t know.

I’ve seen both ends of the spectrum in the clinic. Some people feel their heel pain is much better with cushioning and support when running. Others find it goes away running in their bare feet. The fact is that you will run differently in different shoes. Where the load travels through the foot and the points of stress will change. If one type of shoe encourages you to run in a way that puts a lot of load through the plantar fascia, that will probably hurt more. However, it’s really hard to say which type of shoe will do that.

If you have heel pain, I would suggest choosing your shoes based on comfort. If you find cushioned and/or supportive shoes feel better, wear them. If you find minimalist or zero-drop shoes feel better, go with those.

Running Technique Work

In Part I we discussed that Pohl and colleagues found runners with plantar fasciopathy tended to land with higher impact than those without plantar fasciopathy (Pohl 2009). This suggests that higher impact when running is associated with plantar fasciopathy. These runners already had the problem so it’s difficult to say if it was a cause or an effect. Also, this is the only study I’m aware of that has looked at this particular variable. So all in all we have to interpret these results with caution. However, I have written before about the benefits of reducing impact with running. So it’s definitely worth considering changing your technique to reduce impact if you have plantar fasciopathy (or want to avoid it).

There are risks involved in changing your running technique. You will be changing where the stress goes in your legs and those tissues will need time to adapt. As with any running technique change, it should be implemented very slowly. I have an article that describes in detail how to reduce impact with running.

Shockwave

The use of Electocorporeal Shockwave Therapy (ESWT) or ‘Shockwave’ has become more popular in recent years. Initially this treatment was very expensive as the clinic would have to buy a shockwave unit for a small fortune. Nowadays it’s not that hard to find a local physiotherapy or chiropractic clinic that will offer shockwave treatment for a reasonable price.

So what are we talking about here? Shockwave is a machine with a little applicator that the therapist holds to the affected area. ‘Shockwaves’ are then delivered into the tissue in the hopes that it will cause a little damage or microtrauma in order to initiate a healing response. Shockwaves are basically very fast sound waves like those that planes make when they go beyond the sound barrier. You can get Focused Shockwave (FSW) with a very precise treatment area or Radial Shockwave (RSW) with a bigger treatment area. The treatment itself kind of hurts but there are no known side effects.

This all sounds really cool, but does it work!? Actually, evidence suggests that it does. In 2017 Sun and colleagues performed a meta-analysis of a bunch of studies on shockwave for plantar fasciopathy. This means they took a bunch of previous studies, pooled the results and re-analyzed them. To determine if it worked they had a kind of yes/no criteria. If a subject said that the heel pain first thing in the morning reduced by 50% or came to below 4/10 on the pain scale they said ‘yes – it worked’ for that person. If a subject said the pain didn’t come down that much they said ‘no – it didn’t work’ (Sun 2017).

Basically they found that the real shockwave was about 2.5 times more likely to ‘work’ than a placebo shockwave machine. This seems to go for either FSW or RSW but they are more confident in the results for the FSW. This is actually a really good result considering all of their subjects were suffering from heel pain for more than 12 months and had ‘failed physiotherapy’. They recommended that shockwave be considered a viable option for people who had failed physio and were considering injections or surgery (more on these below).

More interesting for us runners was a study by Rompe in 2003. They looked specifically at shockwave for runners with plantar fasciopathy. They only included people who ran more than 30 miles per week (before the heel pain stopped them obviously). They found that shockwave reduced morning pain from 7/10 to 2/10 on average. The placebo group only improved from 7/10 to 4/10 (Rompe 2003).

I haven’t been able to find any studies on shockwave for acute plantar fasciopathy. All of the above studies used participants who’d had the heel pain for 6 months or more. I found one study that required the participants to have had the problem for only 3 months, but they didn’t give the information about how long their participants actually had the problem. They only showed a very small benefit of shockwave over placebo (1 point on the pain scale). This makes sense because the placebo group we improving so much anyway due to natural history (see above) (Vahdatpour 2012).

All in all, shockwave seems to work pretty well for people who have had heel pain longer than a year. I wouldn’t really recommend it if you have had the problem less than a year. However, if you have ‘failed physio’ and are considering more invasive options like injections or surgery, I’d definitely suggest trying shockwave first. All the studies were done on 3 sessions of shockwave, 1 per week. They used roughly these settings: 2000 pulses per session at 1.6 mJ/mm². Prices will vary obviously, but you should be looking at about $200-$300 in total (for 3 sessions).

Orthotics

There aren’t many good studies looking at the use of orthotics for plantar fasciopathy. The main problem is that they don’t seem to use placebo’s or a ‘no-treatment’ group very much. They tend to compare one type of orthotic to another, or orthotics with some other treatment. Then they say orthotics work just as well as _________ . In their review article in 2015, Lewis and colleagues concluded

“Studies have shown that orthotics, both prefabricated and custom fitted, reduce pain and improve function in adults with acute plantar fasciitis with few risks or side effects.” (Lewis 2015)

Unfortunately, a quick glance at their own table shows that of the studies they used to reach this conclusion, almost half weren’t even looking at orthotics!

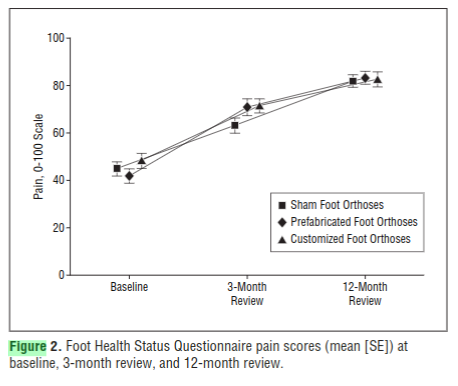

A couple of good studies looked at custom orthotics vs off-the-shelf (prefabricated). This is important because custom orthotics cost around $400 and off-the-shelf orthotics cost around $50. These 2 studies concluded that custom and off-the-shelf both reduce pain equally well after a few months (Landorf 2006, Baldassin 2009).

These studies looking at custom vs off-the-shelf reflect the findings a robust Cochrane review by Hawke in 2008. It concluded that custom orthotics don’t seem to be any better than off-the-shelf orthotics when it comes to treating plantar fasciopathy (Hawke 2008).

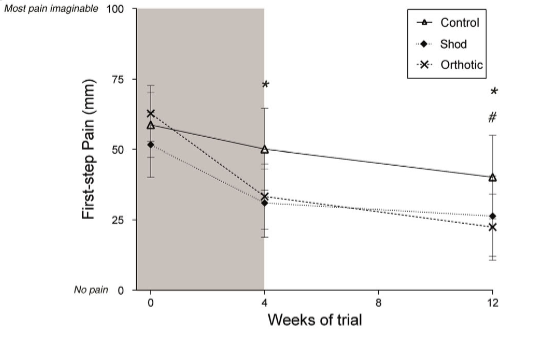

In 2018 Bishop and colleagues did compare a placebo (sham) orthotic to a custom orthotic. The sham orthotic was just a 17mm flat insole. They were looking at people who had had heel pain for about 6 months on average (acute). They found the custom orthotic to be significantly better at reducing first-step-pain than the sham orthotic. Unfortunately they only followed up the subjects for 12 weeks. Again, given the extremely good natural history of acute plantar fasciopathy, there is every reason to think these groups would look a lot more similar by the 12-month mark (Bishop 2018).

Interestingly, they included a group that just got a new pair of shoes (some neutral Asics). If you look at that graph, the new shoe group was doing just about as well as the custom orthotic group by the 12 week mark. Again, this is important in terms of cost. A new pair of Asics might set you back $130, custom orthotics + new shoes will probably cost closer to $500 (the custom orthotic group also got new shoes).

(This isn’t specific advice to buy Asics. The subjects in this study received a pair of neutral Asics so we can only draw conclusions on this type of shoe).

So what can we take away from this study? If you have had heel pain for less than 12 months you could

- Buy some custom orthotics ($400) + new Asics ($130)

- Buy some new Asics ($130)

- Just wait it out ($0)

What you decide to do it totally up to you given your level of discomfort, how restricted you are and your financial situation.

I have not been able to find any evidence that orthotics (custom or off-the-shelf) are any more effective than just waiting if you have had heel pain less than a year. I often try off-the-shelf orthotics with people in the clinic and if they find the pain feels better immediately I suggest using them for 6-12 months and then discarding them. I usually don’t consider custom orthotics unless the problem has been there > 12 months. Even then I would try off-the-shelf first.

Steroid Injection

Steroid injection (corticosteroid injection) is an option sometimes offered to those who have been suffering from plantar fasciopathy for a long time and aren’t getting any better with conventional treatment. Unfortunately, the evidence for using a steroid injection to help with heel pain is pretty weak. Essentially the evidence shows that pain reduces by about 1-2/10 compared to placebo or physio and the effect only lasts about a month (Chen 2018, David 2017, McMillan 2012).

Also, the steroid injection weakens plantar fascia tissue and may lead to increased chance of a plantar fascia rupture. It’s hard to find any statistics on this, but one study mentioned the rate of rupture was as high as 10% (Tatli 2008).

For these reasons, I can’t really recommend a corticosteroid for acute or chronic plantar fasciopathy.

Surgery

Surgery for plantar fasciopathy usually involves cutting the medial band of the plantar fascia itself. The idea is that once that band is cut stress wont be transmitted through that painful part. Unfortunately that does weaken the plantar fascia and can interfere with the windlass mechanism. This decreases the ability of the plantar fascia to help support the arch of the foot and will increase the burden on other structures to support the arch (Thordarson 1997). This is bad news for runners in particular. Using surgery to get rid of plantar fasciopathy only to develop tibialis posterior tendinopathy a year later is essentially just robbing Peter to pay Paul.

In reality, this type of surgery is not usually done on runners but reserved for those unfortunate individuals who have had the heel pain for many years and failed all other conventional treatments. These people are often significantly disabled by the pain and have not been able to run for many years. Surgery is really only considered as a final option.

Whether the surgery works or not is a difficult question to answer looking at the literature. Many papers claim the success rate to be as high as 75-90% (Hake 2000, Davies 1999). However, most of that research comes from case reports. That is like an internal audit a group of surgeons do on their own practice. The methodology is nowhere near as robust as that which is required for a Randomized Control Trial (RCT). This means we have to be extremely cautious in interpreting these results.

Other audit reports were less favourable, for example MacInnes and colleagues concluded that “open plantar fascia release is of questionable clinical value … patients may improve in the natural course of the disease, in spite of surgery” (MacInnes 2016). Confusingly, Davies and colleagues reported 34 of 45 patients went from “severe pain” to “pain-free or mildly-painful” yet only 20 of the patients were satisfied with the outcome … not sure what to make of that.

So, hopefully, it will never come to this. Surgery is an option for people who have had plantar fasciopathy for many years and are really struggling to do regular stuff like walking and working. If you can run at all, you really shouldn’t be considering surgery.

Summary

So there we have it. The good news is that plantar fasciopathy usually gets better on it’s own no matter what within 12 months. The bad news is that it can really reduce your ability to run during that time. There is also a small chance that the symptoms will last more than a year.

If you have only had the problem a few months you have a number of options. You can wait it out. You can do some stretching and strengthening. You can try some heel cups or self massage.

If you have had the problem longer than a year then the news is still reasonably good. The research shows that most people tend to improve over the subsequent 1-2 years. If you want to be more pro-active you can start stretching and strengthening. You could also work on reducing impact with your running technique. You might consider trying some sessions of shockwave or buying some off-the-shelf orthotics. I wouldn’t recommend steroid injections or surgery unless you have exhausted all other options.

If you have any questions or comments please leave them below and I’ll get back to you. Otherwise…

Happy Running