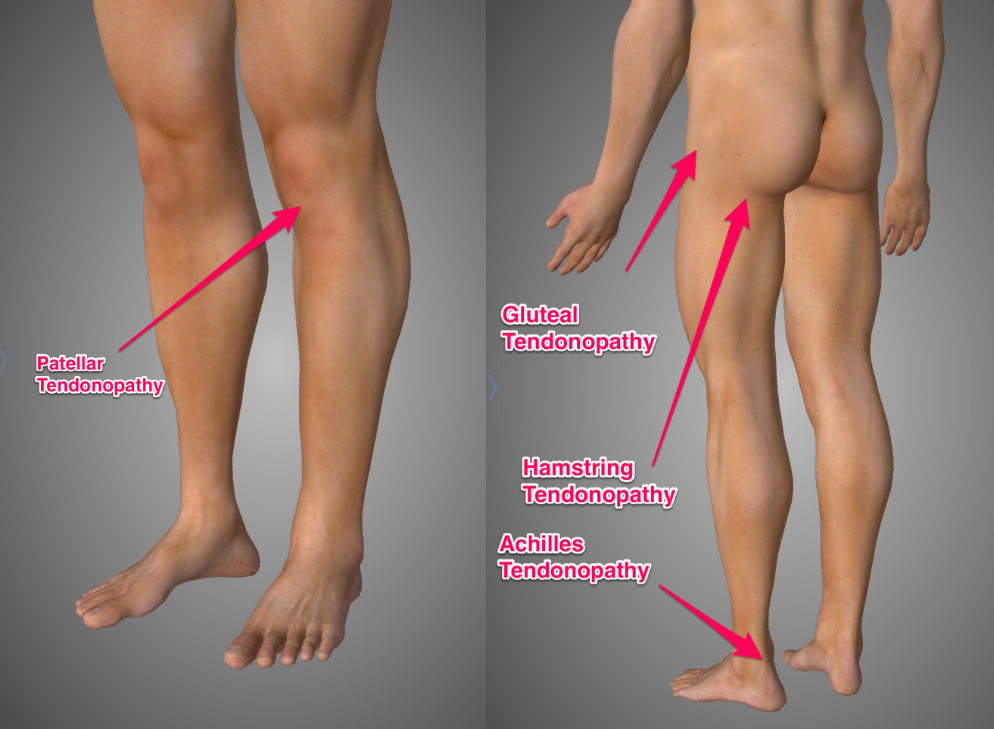

Tendonitis is also known as tendinitis, tendinopathy, tendonopathy, tendinosis or tendonosis. Confusing eh? It’s a common problem for runners. Here are some of the areas runners frequently suffer from tendonitis:

- Achilles tendon (heel)

- Patella tendon (knee)

- Gluteal tendon (side of hip)

- Hamstring tendon (butt crease)

Pain from tendonitis usually comes on immediately with running but will often warm up and feel a bit better as you get going. Once warmed up it can remain relatively painless but will often feel worse the following morning. The pain is usually quite localised, meaning that you can pretty much put your finger on exactly where it hurts.

Tendonitis is a beast of a topic. So I’m going to make this the first in a series of posts about tendonitis in runners. Tendonitis is not the trendy term to use in the sports medicine world right now, so I’m going to use the term tendinopathy for the rest of this article (a little more on that later).

For this first article, we’re going to dig into the underlying pathology (disease process) to help us understand the nature of the problem. In subsequent posts I’ll walk you through the treatment of tendinopathy in general and then go into each specific type of tendinopathy individually.

What is Tendinopathy?

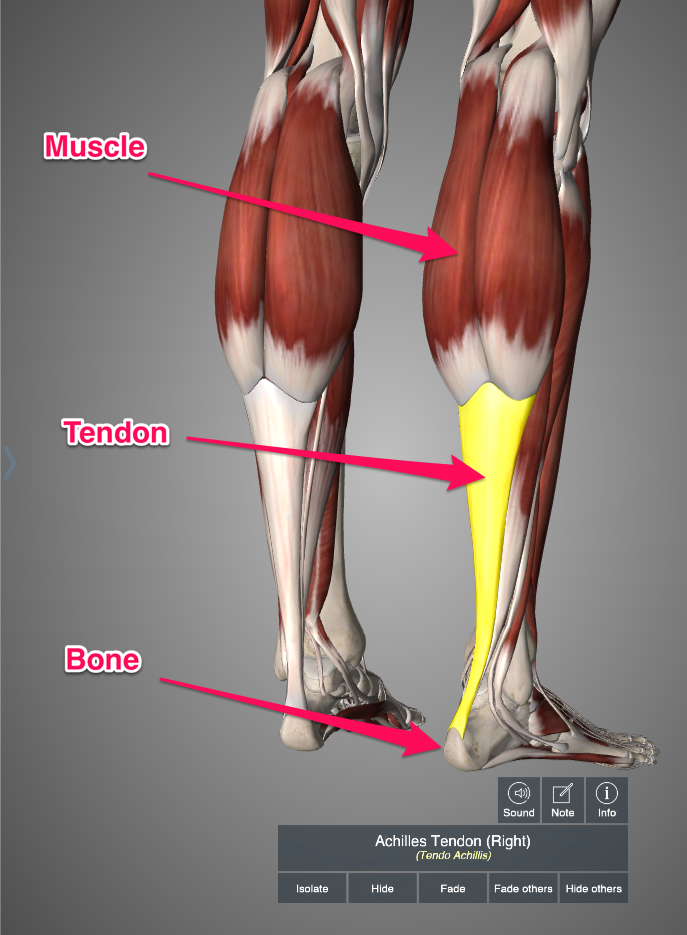

So what are we talking about here? Basically we are talking about tendon pain. The tendon is the strong band of connective tissue that connects your muscles to your bones. Essentially, muscles become tendons before they attach to bones. For this reason the muscle and tendon together are sometimes referred to as the musculotendinous unit.

Tendons differ from muscles in that they do not contract (shorten). If you think of your muscle as an elastic band that can stretch and shorten you can think of your tendons as more like bits of string or rope. Rope doesn’t stretch or shorten, it just stays the same length. It transmits force to the bone to produce movement but it does not generate force (muscles do that).

If we continue to think of tendon like a rope then we can consider the little fibres that make up the rope the same as the little collagen fibres that make up the tendon. These collagen fibres are little strands of protein that are organized in progressively larger bundles to create the tendon:

The job of the tendon is to transmit force generated by the muscle to the bone to produce movement. Take your calf muscle for example. If you stand up on your toes you will contract both calf muscles. The calf muscle will pull the Achilles tendon which will, in turn, pull the calcaneus (heel) bone upwards. Thus lifting your heels off the ground.

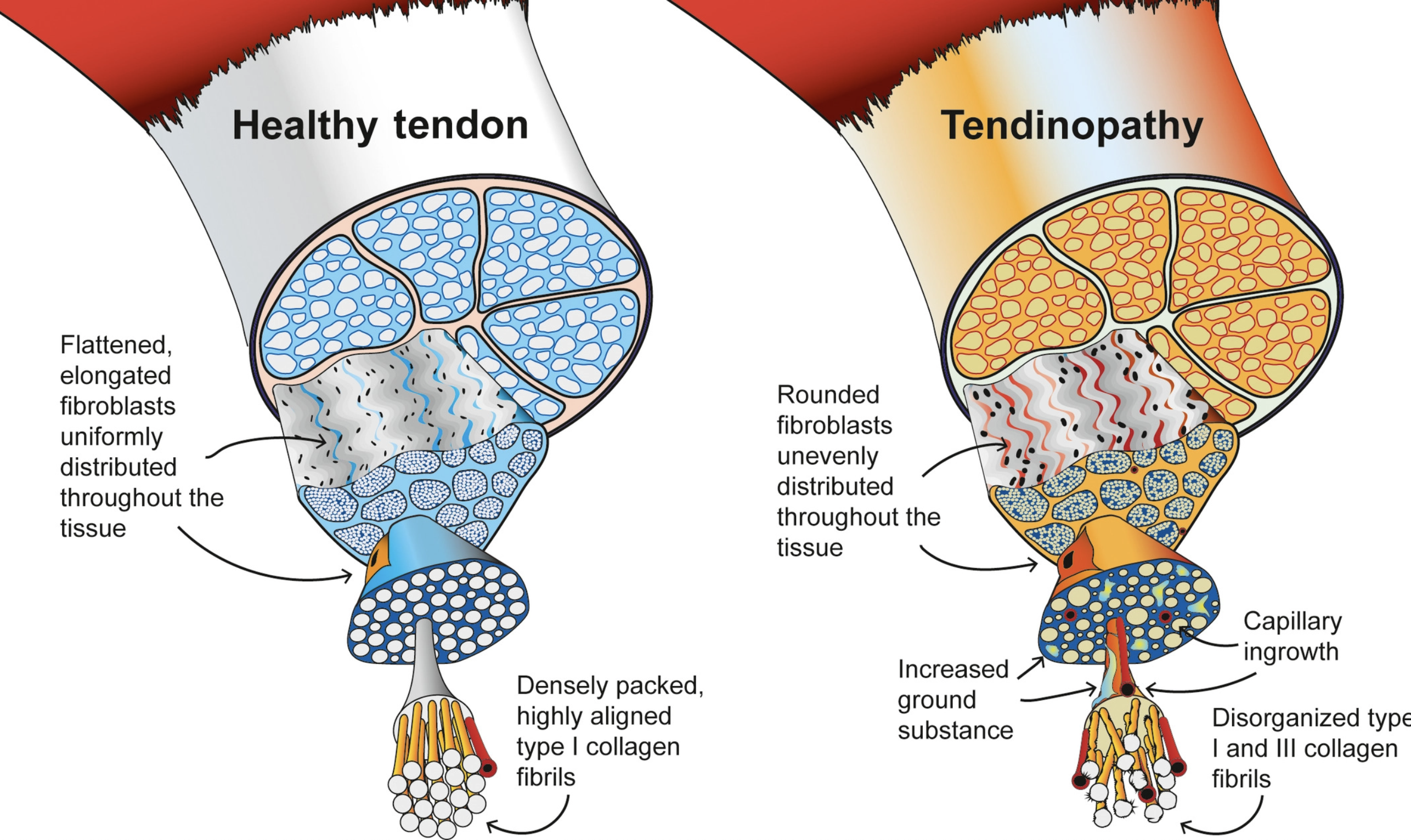

Tendinopathy is a difficult condition to define. There are two features of the condition. One is that the tendon itself will feel painful and the second is that the arrangement of the collagen we discussed above will look a little disorganized on imaging (like ultrasounds scans or MRIs). The difficulty here is that we often come across people with one of those features but not the other. Many people complain of tendon pain but appear to have normal tendons on imaging. Also, many people show signs of collagen disorganization on imaging but are not experiencing any pain (Rio 2013). Here is an image illustrating that collagen disorganization:

To get around this confusion I use my own little criteria that happily seem to agree with those set out by tendon expert Dr Peter Malliares in his article here. My criteria for determining when you have tendinopathy require your symptoms to meet two conditions:

- Pain is local to the tendon (you can point at it with your finger)

- Pain is load dependant (gets worse with loading and better with rest)

In the clinic, I will do more tests to try and confirm or refute that diagnosis, but these are the two most important criteria. Just to clarify, when I say loading I mean anything that causes mechanical stress or load on the tendon. Running will load all of the tendons I mentioned at the beginning of this article and it is usually the activity that provokes the tendon pain. To sum up:

Tendinopathy is local tendon pain that is provoked by loading

I talked about this in a recent podcast episode…

Where is the pain coming from?

If you thought the first question was a little difficult to answer wait till you get a load of this one! For many years tendon pain was attributed to tendon inflammation. That’s where the term tendonitis came from. The suffix ‘itis’ literally means ‘inflammation’. So initial treatments were based around rest, ice and anti-inflammatory medication. That didn’t seem to help most of the time and people often continued to suffer for years with ‘tendonitis’.

So the scientists did a bit more digging and found that the cellular changes in painful tendons didn’t really seem to match the profile for typical inflammation (Abate 2009). When you sprain your ankle you get a big swollen ankle. That’s the first stage of the healing process. The chemical soup that makes up the fluid in this injury does all sorts of clever stuff to get the ball rolling on healing the injury. You take it easy for a couple of months while the injury heals and then you can get back to running. In tendinopathy it doesn’t seem to work that way at all. There is no big inflammatory response in the tendon and if you take it easy for a couple of months when you try running again it will probably be worse than when it started!

In this way, tendons just don’t seem to get better on their own the way ligament sprains or muscle strains do. The body just seems to ignore them. They don’t follow the typical pattern for an ‘inflammation’ injury and so the medical world had to start to think about them differently. This is when the term tendinopathy became more popular. The suffix ‘pathy’ means ‘suffering or disease’. So now tendon pain is technically ‘tendon suffering’, which I think is quite funny.

Tendon Pain (Part One)

So if the pain in tendinopathy is not coming from inflammation, where is it coming from? A few of the brightest minds in tendinopathy and pain science research from down under wrote an article on this in 2013 titled The Pain of Tendinopathy: Physiological or Pathophysiological? I read it a few times and managed to give myself a headache.

The article seems to suggest that the pain is related to lots of different changes in the cellular and chemical environment of the tendon. This leads to changes in ion channels (cellular gates) that stimulate local nociceptors (danger sensors) that convey that information to the Central Nervous System CNS (brain and spinal cord). The CNS then decides if that danger message is important or not. If it decides that it is then you will feel pain in the tendon.

This CNS involvement is important to help us understand some of the funky aspects of tendon pain. One is the fact that people often experience tendon pain on both sides of the body. We usually explain this by saying “It must be because you’re using that side more now”. However, baseball pitchers often get shoulder tendon pain in the non-throwing arm. Tennis players also often get tendon pain in the elbow of the non-dominant arm. These things are hard to explain if we just think of mechanical use. However, if we consider that sensitization of the CNS may be occurring then that would explain these funky experiences.

Another theory put forth in the article was that the CNS becomes sensitized to loading of that tendon. So when you load the tendon X amount the CNS actually thinks you are loading it XX amount. That misinformation is interpreted by the CNS as dangerous and so you feel pain in your tendon (pain is the CNS way of saying “whooaw…careful now”) This would help explain why the pain only comes on with higher loading (like running). This ‘mistake’ in processing might also explain why tendons without any changes in the collagen organization (i.e. they look normal) can be very painful (Rio 2013).

Is your head hurting now too?

I’ll try and simplify it. Tendon pain comes from the tendon itself but not due to inflammation. Tendon pain can occur in tendons with disorganized collagen but also in tendons that look ‘normal’ on scans like ultrasound and MRI. The reason tendons hurt may be related to changes in the nervous system as well as changes in the tendon tissue itself

I’m not actually sure that’s any simpler!

Enter the Continuum Model of Tendon Pathology

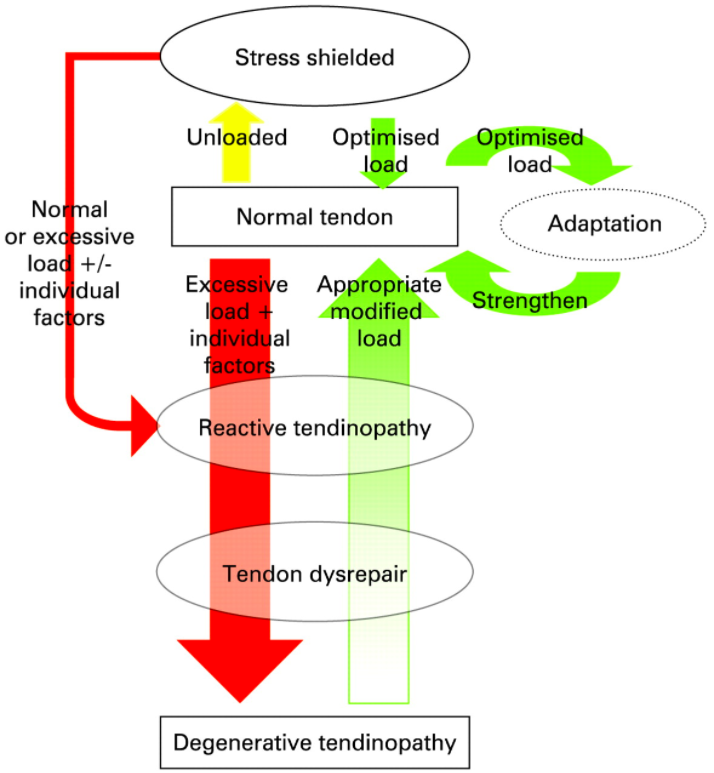

In 2009 a couple of tendon experts from Australia (all the good tendon stuff seems to come from down under) wrote a paper in which they proposed a continuum theory for how tendons become tendonopathic. This paper focused primarily on the changes in the tissue and not as much on the actual complexity of the pain (as discussed above). The theory proposes that tendons will degenerate (become crappy) when overloaded. When this happens it will follow a three step process of increasing severity (Cook 2009):

- Reactive

- Dysrepair

- Degeneration

The theory goes that tendons start normal and will become reactive (irritated) if the tendon is overloaded. Continued overloading will lead to dysrepair (bad healing). If this continues long enough degeneration (breakdown) will occur. If this continues then eventually the tendon will rupture (break). Yikes!

They coined the term ‘stress shielded’ to describe the natural weakening of tendons that don’t get loaded enough. As the saying goes “Use it or lose it”. Stress shielded tendons have become weaker and are thus more vulnerable to being overloaded. So the key to healthy tendons is to load them ‘not too much, but not too little’. Just like baby bear’s porridge, ‘just right’. I talk A LOT about this concept of adaptation.

Reactive Tendinopathy

Reactive tendinopathy is an acute irritation of the tendon, usually in response to acute overload. The classic example is a runner who switches to minimalist shoes and runs a 10k on the first try. The Achilles tendon hurts like hell as it has been acutely overloaded and become reactive. Confusingly, the tendon does actually often ‘plump up’ in reactive tendinopathy. This can look a lot like inflammation but it’s actually quite different on a cellular level.

The tendon has deliberately made itself ‘fatter’ to increase its cross-sectional area. This reduces the stress by increasing the area over which the force is being distributed. Weird eh? It’s like an emergency measure to prevent tendon rupture. Importantly, in this stage the collagen fibres maintain their integrity and there is no real evidence of disorganization. So if the overloading of the tendon doesn’t continue, the tendon can just go back to normal.

Dysrepair

This happens if the overloading continues. The tendon is attempting to adapt to the load, but it can’t keep up so it does a shoddy job. The collagen fibres start to look a bit disorganized (this is called matrix disorganization). Instead of being lined up in tight bunches like a steel cable they are more wiggly and haphazard in their appearance. An ultrasound scan at this stage will start to show little gaps between the collagen fibres in random places that look like little holes (hypoechoic areas). We also start to see some funky new stuff in the tendon like blood vessels and nerves that aren’t normally there (neurovascularization).

If the loading is reduced so the tendon is no longer being overloaded then it is probably still capable of repairing itself at this stage.

Degeneration

If the overloading continues for long enough the tendinopathy will progress to this stage. Now the tendon has become badly damaged. The collagen fibres are very disorganized and there are areas of the tendon with little collagen to see. There are random blood vessels and dead cells here there and everywhere. There are still areas of collagen continuity in the tendon which allows the tendon to continue functioning. On ultrasound scan there are more hypoechoic areas (holes) and lots of those blood vessels and nerves in the wrong place.

If the overload is stopped at this stage the tendon probably can’t heal itself anymore. If the overload continues then there is a risk of rupture. About 97% of tendons that rupture show evidence of degeneration prior to the rupture (Cook 2009).

Tendon Pain (Part Two)

Oddly enough the changes in the tendon described above don’t correlate well with pain. As I mentioned earlier many seemingly normal tendons that don’t show any of the changes I just described can be painful. Conversely, tendons showing significant signs of degeneration are often pain-free. In fact, up to two thirds of people who rupture a tendon feel no pain at all prior to the rupture (Cook 2009).

The weird thing about tendinopathy is that you can have a lot of tendon pain during any of the stages described above or you can have none at all! This may sound crazy but it’s not as unusual as you might think. For many years now the medical world has been trying to make sense of the lack of correlation between tissue damage and pain. From low back pain to knee arthritis to shin splints to rotator cuff tears there is literally bucket loads of studies showing a poor correlation between tissue damage and pain. Weird eh?

The weirdness of pain is too big a topic to unpack here. However, I wanted to point all of this out to give hope to those of you struggling with tendinopathy who have had an ultrasound or an MRI scan that showed ‘degeneration’ or ‘partial tearing’. The human body has an AMAZING capacity to adapt to damaged areas and continue to function. We’ll be talking about that more in the next article in this series.

Summary

Tendon pain used to be called tendonitis. Recently it was discovered that it wasn’t so much of an inflammation of the tendon so the name was changed to tendinopathy. Tendinopathy refers to changes in the tendon that occur as a result of overloading. These changes are more likely in weak tendons that have been ‘stress shielded’. The changes in the tendon can be divided into three stages: reactive, disrepair and degeneration. Tendon pain can be experienced with or without changes in the tendon. This is probably due to changes in the nervous system.

Click here to read part two. We’re going to talk about how to fix it!