Good Running Form

Running form varies wildly from runner to runner. So how do you know if you have good running form? There are many, many people on the internet teaching “proper running form” but what I want to know is, what does the evidence say?

Over the years, I’ve read dozens of research studies looking at running form. These studies are trying to identify the variables that might lead to improved performance or reduced injury risk. In all of this research, I have noticed a few commonalities. A few key parts of running form that seem to keep cropping up as being related to performance or injury risk. What’s more exciting, is that I think I’ve identified a single variable that would positively or negatively affect all of those other variables.

So we probably only need to look at one thing in order to decide if we have good running form. If you want to know what it is, well, read on.

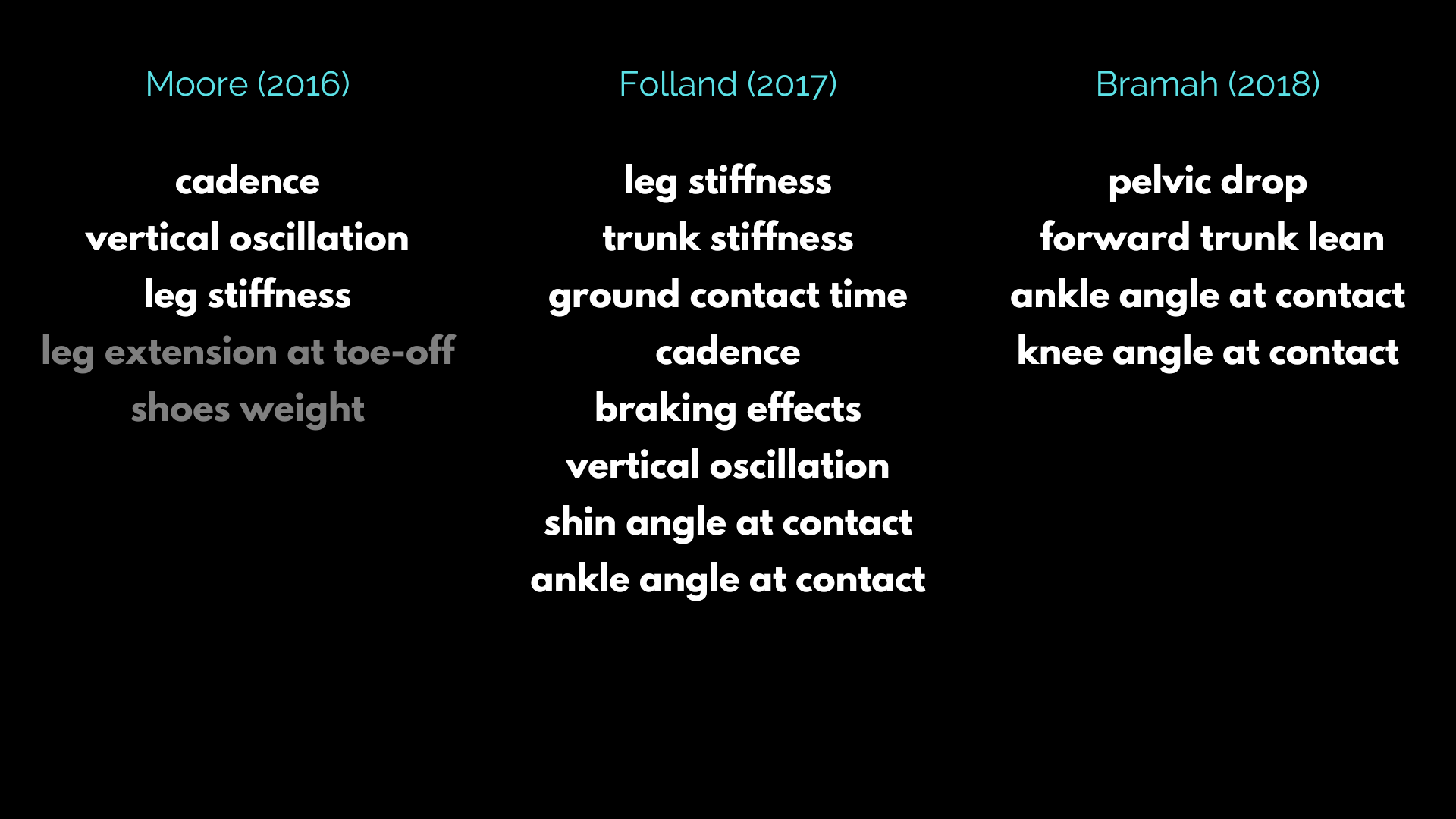

As I said, I’ve read dozens of studies on running form and there are hundreds out there with more being published every month. I don’t want to present this as the final statement on running form, but rather, as a solid starting point that will give you some simple, practical ways to start looking at your own technique. In today’s article, I’m going to lean heavily on 3 papers that I think do a pretty good job of representing the current research available on running technique.

First up, a fantastic 2016 review of all of the research to date that examined the link between running form and running economy by Dr. Izzy Moore (Moore 2016). Secondly, a 2017 study that looked at 97 runners to identify links between aspects of their running form and their performance by Dr. Jonathan Folland (Folland 2017). And finally, a 2018 study from Dr. Chris Bramah looking at 72 injured and 36 uninjured runners to identify aspects of running form that seemed to be more prevalent in the injured runners (Bramah 2018).

These three papers were very influential in the running biomechanics and Physiotherapy world. I’m also excited to report that all three came from my home country! If we look at all of the variables identified as negatively influencing performance or injury risk from the three studies, we can see a few that keep cropping up. They use different terms and ways of measuring these things in the papers, but I’m going to try and simplify this by grouping them into four specific running technique errors:

- Overstriding

- High vertical oscillation

- Knock knees

- Dropped pelvis

Let’s go through them one at a time, first up, overstriding.

Related Service…

Overstriding

Overstriding simply means landing your foot too far out in front of you when you’re running. However, since we have to land the foot at least a little bit in front of us to go anywhere, it can be hard to define what exactly constitutes overstriding. So, how do you know if you’re overstriding? Thankfully, there is quite a simple method.

First off, you’ll need to get a side-on video of you running on a treadmill. Make sure that the camera is pointing at you directly side-on and not off to an angle. If your phone camera has a “slo-mo” setting, use that. You can easily do this by putting your phone in a running shoe to hold it upright and placing it on a chair a few feet off to the side of the treadmill.

Once you have your video, you’ll need to scrub through and pause it at the point where you’re foot first contacts the ground. Now you want to look at the angle of your shin bone. As you land on your foot, your shin bone should be pretty much vertical. If it is angled backwards, this means you’re overstriding and landing too far out in front.

Vertical Oscillation

Next up, we’re looking for higher vertical oscillation. This means how much you bounce up and down as you run. If you’re spending a lot of energy jumping up in the air, you’re going to be less efficient at propelling yourself forwards. However, you can’t just glide along without bouncing up and down at all. There is a certain amount of vertical movement that is needed to propel yourself forward, we just don’t want it to be excessive.

Think of throwing a ball as far as you can. You won’t throw it straight up in the air as it will just come back down on your head. You also wouldn’t throw it dead horizontal. There is an optimum angle of trajectory that would have the ball travel the furthest. That’s what we’re trying to do as we push off one foot to propel ourselves forward as we run.

Both Moore and Folland identified excessive vertical oscillation as being associated with poorer running economy and worse running performance (Moore 2016, Folland 2017). It’s really hard to define how much vertical oscillation is too much, as it depends how tall you are. However, as you’ll see by the end of the article, we don’t need to measure this one to get it in the optimal range.

Hip Drop and Knock Knees

Next up, we’re looking for knock knees. You’re going to take a video of yourself running on a treadmill shot from directly behind you. Just take your phone and wedge it upright in a running shoe again. Place it on a chair behind the treadmill pointing directly at you. Make sure it is square-on again, it can’t be off to an angle. Again, if your phone camera has a “slo-mo” setting, use that.

Take the video and then scrub through until to point in your gait cycle when the knees pass each other. We want to see some air between the knees. If the knees are touching, I call that knock knee running but in research papers, they call it hip adduction. Keep the video paused at that point and look at your pelvis. It wants to be level. Meaning that if you draw a line across your pelvis from left to right, it should be horizontal. If it is tilted down to one side, it is known as a contralateral pelvic drop in the research, but I just call it a pelvic drop. In his 2018 study, Dr. Bramah concluded that pelvic drop and knock-knee running were associated with increased injury risk (Bramah 2018).

After shooting a couple of videos of yourself running on a treadmill and going through the steps above, you can easily find out if you have good running form. Essentially, if you’re not overstriding, bouncing too much, knocking your knees or dropping your pelvis, you have good running form. But what if you are doing one of those things? What if you’re doing all of them!?

Well, you’re in luck. The first important thing to remember is that while these running technique errors are associated with increased injury risk and worse performance. They are not destiny. Many runners do all of these things and hardly ever get injured and perform really well. So when it comes to optimizing your running form, remember to take a fairly chilled approach. You’re trying to stack the deck in your favour when it comes to avoiding injuries and improving performance, but this is far from the only variable at play.

Some more good news is that I believe there is a single factor that links all of these running technique errors together. Something that we can easily measure and manipulate in order to optimize our running form…cadence.

Cadence

Your cadence is also known as your step rate. It is simply the number of steps you take each minute. Most elite runners have a higher cadence than most recreational runners, albeit with some overlap. If you use a GPS watch, you can probably just have a look at the data from your last run to find your average cadence. Alternatively, you can count how many steps you take in 6 seconds and then multiply it by 10.

Generally speaking, a higher cadence would be over 180 steps per minute. 170 to 180 would be moderate and below 170 would be fairly low. Obviously, this will depend on the speed you’re running, but it’s a good rule of thumb. Your cadence only usually increases a few steps per minute when you increase your pace. The interesting thing is that a low cadence seems to be associated with those running technique errors that I mentioned earlier. Overstriding, higher vertical oscillation, knock knees and pelvic drop. Conversely, a higher cadence seems to be associated with not doing those things.

Essentially, when you’re taking more steps per minute, you don’t have time to sink down each step. Your knee doesn’t have time to move towards the other one and the pelvis doesn’t have time to drop. You have to hit the ground and bounce off it immediately. As I mentioned earlier, this is actually called increasing leg stiffness in the research another variable that has been associated with the improved running economy (Moore 2016, Folland 2017).

Secondly, when you increase your cadence, you don’t have time to jump up in the air so high, this prevents excessive vertical oscillation. And finally, when you have a higher cadence, you don’t have time to reach out so far in front of you with each step, preventing overstriding. Happily, this also helps correct some of the other things that have been associated with increased injury risk, like having the toes pointed up too much and the knee too straight at initial contact (Bramah 2018).

In fact, of the 17 variables identified in these 3 studies, I would argue that a higher running cadence would help optimize as many as 15 of them. So, if you’ve identified that you are making some of the running technique errors mentioned above, and your cadence is a bit low, increasing your cadence is a reasonable way to try and improve them.

How to Optimize your Running Form

Let’s use a fictional runner named Carrie to help us understand the method. Carrie takes the videos of herself running from the side and from behind as I described earlier. She notices that she’s overstriding and has a slight pelvic drop. She looks at the last few runs on her Garmin and sees that her average cadence is usually around 155 steps per minute.

Carrie decides that she wants to increase her cadence to try and help improve her running form. So she downloads a metronome app and sets it to 155 bpm, she sets the metronome so every fourth beep is at a higher pitch. As she runs along, she’s sure her cadence is 155 as her left foot always touches down with the funny beep. Carrie increases the speed of the metronome by around 10% to 170 bpm. Then she tries to match her footsteps to the beat. She is having a hard time and notices that her left foot doesn’t always hit on the funny beep.

So Carrie decides to try a 5% increase and sets the metronome to 162 bpm. She finds that she can keep to this beat fairly easily and she knows that her cadence is 165 bpm as the funny beep is always in line with her left foot strike. Carrie practices with her metronome app set at 165 bpm for 1 minute for each kilometre she runs for 4 weeks. Then she takes the two videos from behind and the side again. She see that she is overstriding a bit less but the pelvic drop is still pretty noticeable.

She has another go at trying to match the 170 bpm metronome and finds that she can do it fairly easily now. So she practices that for 1 minute out of each kilometre for the next 4 weeks. When Carrie takes the videos again. For the side on video, she looks at her shin when she strikes the ground and sees that it is pretty much vertical, so she’s confident that she’s not overstriding anymore. Then she looks at the video shot from behind and looks at her pelvic level as her knees pass each other. It looks pretty much horizontal now so she happy that she’s addressed her pelvic drop.

Looking at her Garmin data for her last few runs, she sees that her average cadence has been around 165 bpm for most of the run. It would seem that her step rate has been higher through the whole run, not just during the 1-minute interval when she has the metronome on. So Carrie decides to leave the metronome on for an entire run at 170 and see how it feels. She finds that pretty easy, as she has spent the last 8 weeks getting her legs used to the faster turnover.

Conclusion

This is a simple example of how to do a basic analysis of your own running form and apply a simple intervention to increase your cadence if needed. However, running technique analysis is more complicated than this. We need to consider things like your injury history, performance goals, gender, age, and all sorts of other things. If you’re interested in looking at your running technique in order to help you recover from/avoid injury and improve performance, you might be interested in doing an online running technique analysis with me. Just click below for more information…

Discussed in this episode…

Click the link to jump to that part of the video.

- 00:01:54 What does the evidence say?

- 00:03:11 Overstriding

- 00:04:23 Vertical Oscillation

- 00:05:40 Knock Knees and Dropped Pelvis

- 00:07:17 What is good running form?

- 00:07:55 Cadence

- 00:10:43 How to fix your running form

Cool stuff mentioned in the show…