What is Pronation?

I just tried googling this term. All of the top 5 links were discussing how “overpronation” causes injuries and claiming that selecting the correct supportive running shoe will prevent these injuries. Of course, they also provide links for places to buy those shoes. All I asked was “What is pronation?” and immediately people are trying to sell me shoes!

This little story illustrates the major problem with trying to understand whether pronation is an important thing for runners to think about. As soon as you mention pronation, you will get people on one side saying it’s terrible and you need supportive footwear to help you “control” it (link to my supportive footwear shop). On the other side, you will get someone telling you pronation is a natural mechanism for cushioning impact forces, the last thing you want to do is “control” it (link to my minimalist footwear shop). In this article, I hope to cut through some of the noise and just give you the current science.

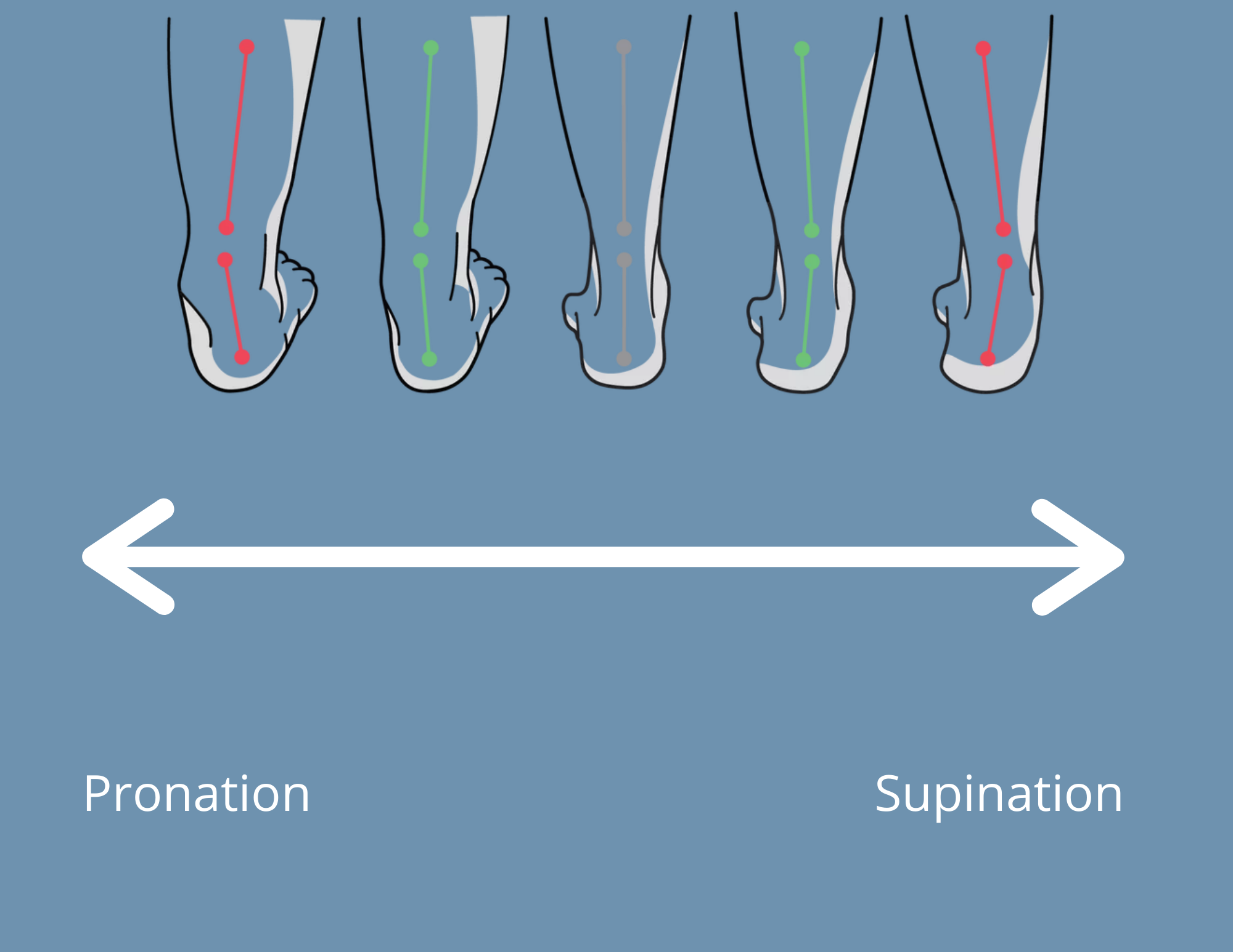

So … What is Pronation? It’s just the rolling in that your foot does when you walk or run. That’s it. It involves the medial arch of your foot flattening out a bit. Everyone’s foot does it to a certain extent. Some more than others. Imagine a spectrum very little pronation (inward roll) on the right and lots of pronation (inward roll) on the left.

Pronation is actually made up of a combination of different movements at different joints. Dorsiflexion at the ankle, eversion at the subtalar joint and abduction at the forefoot. I’m going to try and keep it simple so I’ll leave it at that. If you would like to clarify what the movements are this article from Physiopedia explains it nicely.

The rolling in of the foot with concurrent flattening of the arch known as pronation is in fact a perfectly normal movement. Just the same as extending your elbow, turning your head or flexing your knee. Pronating your foot is just one of hundreds of movements that our body can do. It’s not bad or good in and of itself.

What is Overpronation?

Typing that into google is another quick way to get yourself pitched a variety of different products. You will also be told quite confidently that overpronation causes injuries and needs to be corrected in some way. You would think we had bucket loads of evidence proving the link between overpronation and injuries (spoiler alert, we don’t). However, before we get into whether or not overpronation actually causes injuries, can we at least define what exactly is overpronation?

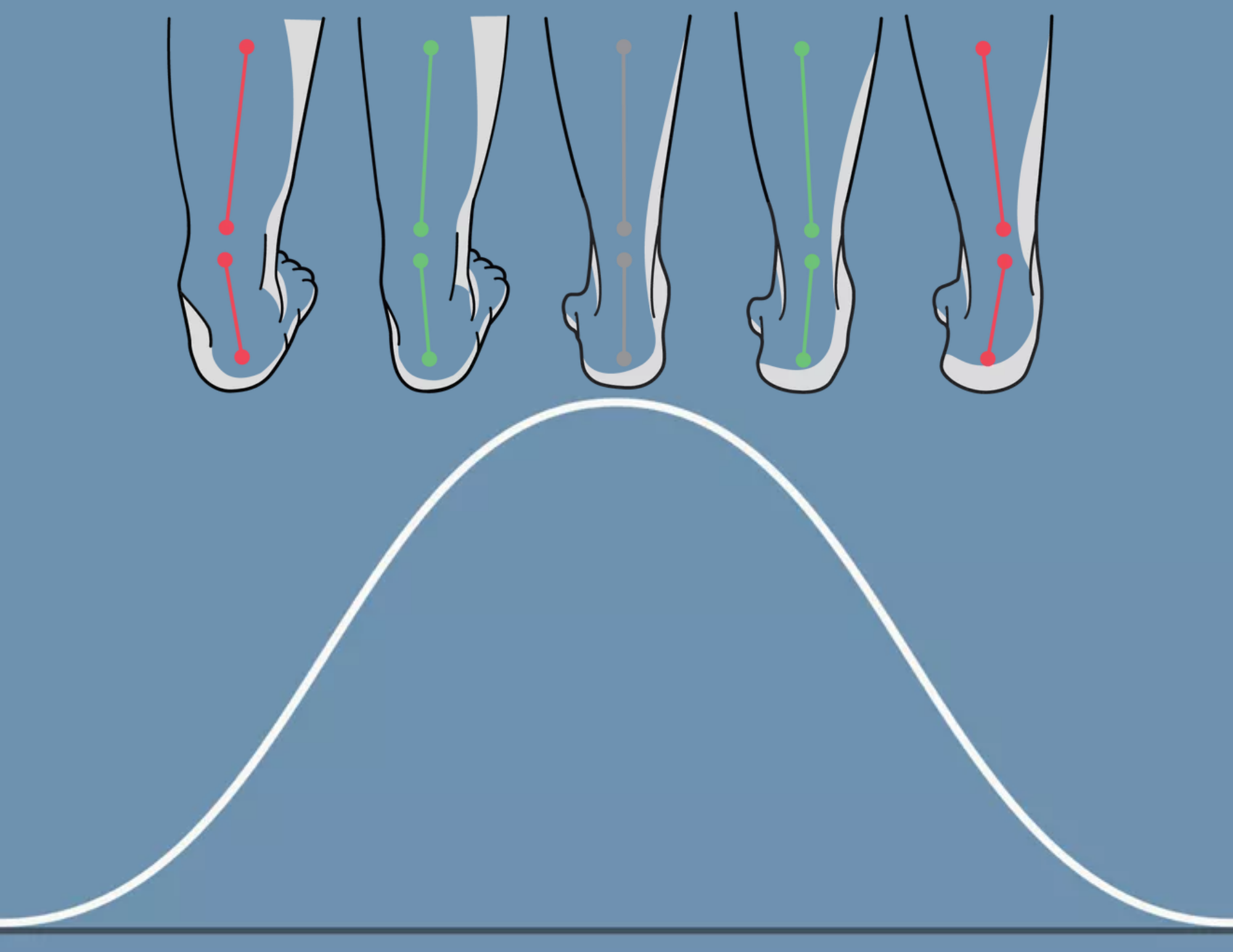

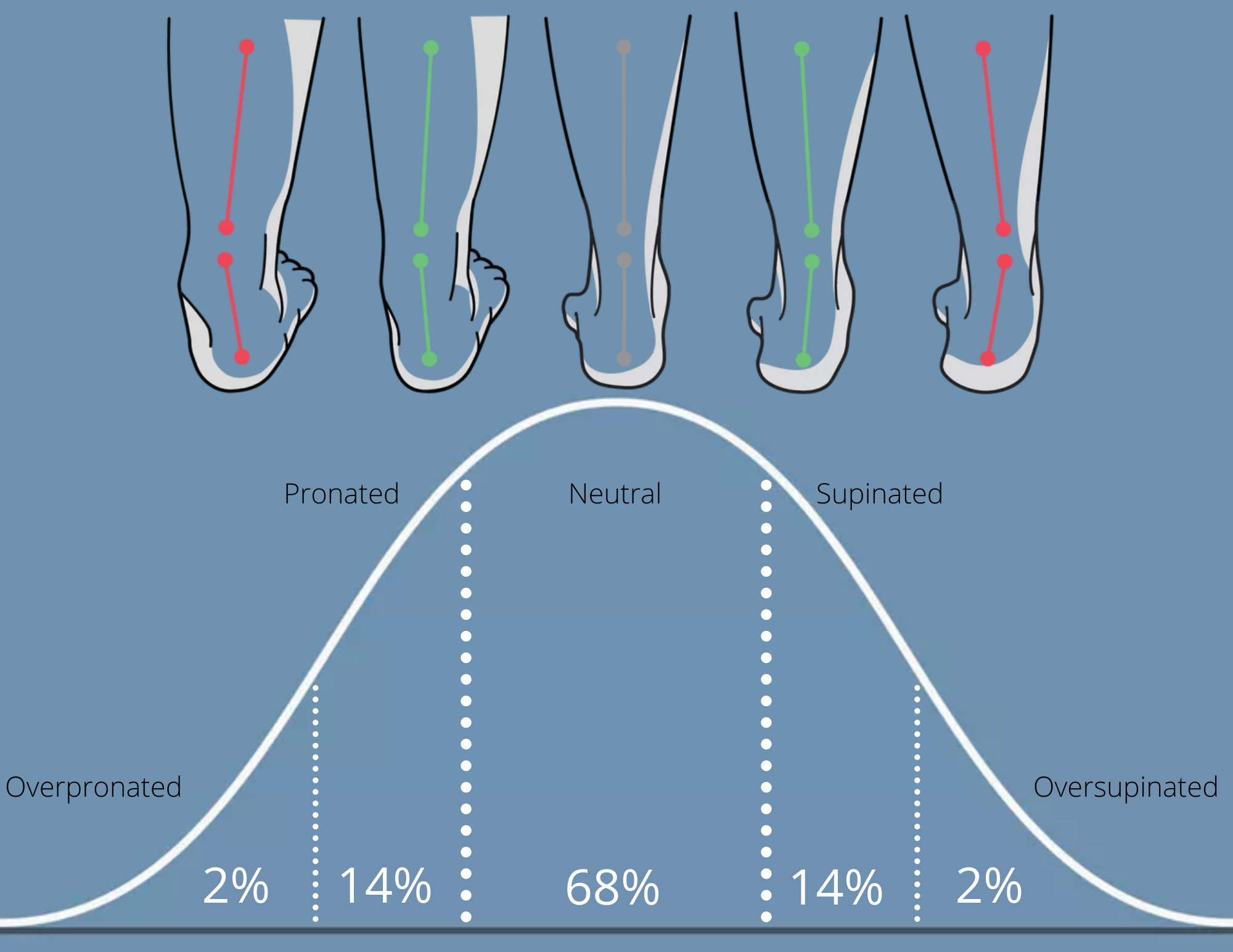

So let’s just think about standing posture first. You stand in front of a clinician of some sort and they look at the posture of your feet. They may say “you have a neutral foot posture” or “you have a pronated foot posture”. Here they are referring to the posture of your foot in static stance. To define “normal” and “abnormal” we can put all of the different foot postures seen in standing on a continuum. We’ll expect to see a bell curve with most people having similar foot postures and some outliers at either end.

Then we’ll take the mean (average) value and add 2 standard deviations above and below it. Finally we’ll give the different postures a name: overpronated, pronated, neutral, supinated and oversupinated.

Now, here is the important part. In human beings there is a wide variety of postures for every part of the body including the foot. When everyone is spread over a continuum like this we define “normal” as “pretty much average”. “Pretty much average” in statistics is 2 standard deviations either side of the mean (average). It’s hard to explain but it looks like this.

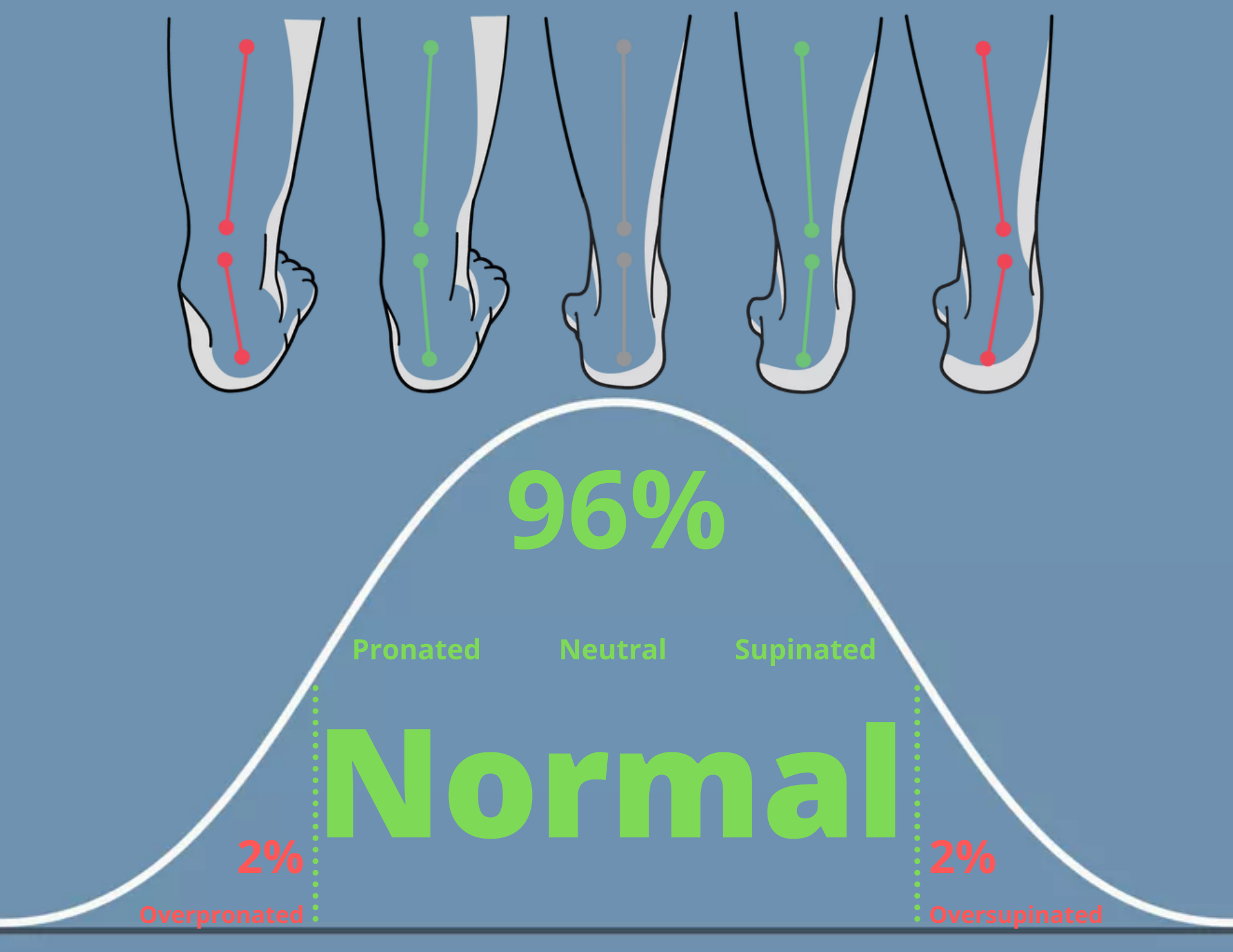

Now it’s really easy to see that the vast majority of people have a “normal” foot posture. Only 2% at one extreme have overpronated feet and 2% at the other extreme have oversupinated feet. So only 2 out of every 100 runners truly has overpronated feet. Yet this topic has had so much time and research dedicated to it! If you take nothing else from this article please remember this:

There is a 96% chance that your foot posture is totally normal

Does Pronation cause Running Injuries?

When we walk or run we usually hit the ground in some degree of supination. Supination is the opposite movement to pronation. It’s the rolling out and raising of the arch. A simplistic summary of foot biomechanics during gait (walking or running) would be:

- Landing in supination

- Rolling in to some pronation to cushion the impact

- Rolling back out into supination to provide a rigid foot to push off with

As we land when we run our foot will start to pronate in order to help absorb the impact. There is an internal rotation of the tibia (shin bone) coupled with this pronation. The theory goes that excessive internal rotation of the tibia will create a large torque that will travel up to the knee and hip. This would increase stress in the leg in different places and could lead to injury (Ferber 2009).

Now, the question is, does that increase in stress manifest injuries? Well, we know that the body has an incredible capacity to adapt. We need to know if pronation or overpronation just puts so much extra stress through the leg that we can’t adapt to that stress and an injury will result. The injury might be a stress fracture or a tendinopathy or runners knee. If pronation or overpronation results in too much stress then runners who pronate or overpronate should be getting more injuries than those who don’t right?

A number of researchers have looked into this over the years. There has been so much research done on this that some other researchers have been able to do systematic reviews of all of the research so it can be summed up. In 2014 a group of researchers from the University of London reviewed 21 studies encompassing 6228 people. They reported that the studies showed pronation was linked to medial tibial stress syndrome (shin splints) and it might be linked to patellofemoral pain (runners knee). However, they stated that the effect size was small – meaning that pronation only increases the risk of these injuries by a small amount (Neal 2014).

The findings of the above review conflict with those of Tong 2013 who also did a systematic review of the literature but found a “significant association of HA (High Arch) and FF (Flat Foot) types with lower extremity injuries” although they conceded that “the strength of this relationship is low”. It’s difficult to account for the different findings of the two reviews.

Also in 2014, the same group of researchers from London published a review of the literature that looked at dynamic foot function. These studies measured how the foot was moving during the gait cycle. They didn’t find anything conclusive to say that the pronation we can observe during gait (kinematics) relates to injury. They did find a little bit of evidence that linked changes in something called plantar pressures to developing Achilles tendinopathy or patellofemoral pain. You’ll need fancy equipment to measure plantar pressures and they concluded there was only “limited to very limited” evidence to connect plantar pressure patterns to injury (Dowling 2014). We’ll have to wait for more research here.

Foot Posture in Runners

For many years, we believed pronation and overpronation were likely to cause injuries by twisting the tibia (shin) and increasing the stress in the leg. That’s where the idea of ‘motion control’ shoes came from. They were designed to reduce pronation, increase stability and thereby, reduce running injuries. That same line of thinking also led to the belief that those at the other end of the spectrum, the supinators, were also more likely to get injured. The theory here being that they lacked the shock absorbing prowess of the pronators. So they must need more cushioning. The mantra went:

Motion Control for the Pronators, Cushioning for the Supinators

A 2005 study classified 131 triathletes as overpronators, neutrals and oversupinators. The 2% at either end of our spectrum mentioned above made up the overpronators and oversupinators. Asking them about their injury history they found that the oversupinators actually got injured more often. There was no relationship between pronation and injury (Burns 2005).

By 2014 the evidence was mounting that this proposed connection between pronation and injuries wasn’t as definitive as we thought. Researchers in Denmark decided to challenge the theory directly. They assessed the foot posture of 927 runners and gave all of them neutral shoes. Since the pronators didn’t have their motion control shoes we would expect them to get loads of injuries right? Well, they didn’t. The overpronators, pronators, neutral, supinators and oversupinators all got injured about the same amount (the pronators actually got injured a bit less!) (Nielson 2014).

More recently, Messier and his colleagues from North Carolina decided to grab a big group of runners, do a bunch of measurements and then follow them for 2 years and see if any of the measurements were associated with more injuries. They took 300 runners and measured loads of stuff: flexibility, posture, arch height, strength, training habits, running technique and psychological well being. Of all of these things, can you guess which one actually correlated with more injuries?

Psychological Well Being!

Yeh! It shocked me too. Not their training habits, running technique, strength or posture. Where their head is at! They used a couple of Psychosocial questionnaires to measure how the runners we feeling (SF-12 and PANAS). Scoring poorly on these was predictive of higher injury rates whereas all of those biomechanical measurements weren’t. Crazy eh? They did find that higher ‘knee stiffness’ was associated with more injuries, but they were measuring the internal forces. So again, you need fancy expensive equipment for that (Messier 2018).

Incidentally, they did a really cool video to share their research findings with a larger audience. I think this is a great idea and I hope to see more of these in the future:

Clearly we really need to rethink the way we look at running injuries. It’s not as simple as looking at a car and saying ‘the wheel alignment is off so that front left tire is going to wear out’. We humans are complicated beasts. Hopefully this study will open the door to more research like this in the future to help us better understand the connections between psychological well being and injuries.

The important takeaway for us in this study is that pronation, yet again, was measured and found to be unrelated to the development of running injuries.

So is Pronation bad or not?

Well, maybe, or yes, actually, maybe no.

Some research suggests there may be a slight relationship between more pronation and some injuries. However, other research found pronators get injured about the same amount as everybody else. Other research showed that pronators get injured less than others. Some research found the supinators are the ones who get injured more and the pronators were fine.

Confusing eh? I’ve spent most of this year reading a stack of articles about foot posture and its relationship with injuries. My biggest takeaway is that the research found mixed results. When they did find links between foot posture (pronation or supination) and injuries, the link tended to be pretty small.

I know this isn’t much of a conclusion. Perhaps I’ll be able to take a firmer stance at some point in the future. However, I have a feeling that future research on this topic may find mixed results again. What I will say is that if having a pronated foot posture was really bad then the research would show time and time again a massive link between pronation and injuries. It would be a ‘barn-door obvious’ link. That is clearly not the case.

I plan to write my next article on running shoes and how they might link to injuries. I have a feeling the water is going to be just as muddy in that area. Stay tuned for that one.

Encore

I just stumbled across an excellent video from Kevin Maggs of Running Reform. It talks about alot of the research discussed above and more. You can follow Kevin on Twitter @runningreform.