Some of the most common running injuries include patellofemoral pain (runner’s knee), plantar fasciopathy, shin splints, Iliotibial Band (ITB) syndrome, Achilles tendonopathy (tendonitis), patellar tendonopathy and hamstring tendonopathy.

All of these injuries have one thing in common; they are all overuse injuries. Running overuse injuries happen when the tissues involved were not able to tolerate the mechanical loads placed upon them by running. Now, you may be thinking “if it is a running overuse injury, I must need to rest, right?”.

Unfortunately, rest is very good for making you weak and deconditioned. If you have read my previous post on Adaptation, then you know exactly what I am talking about. Let’s use the most common running overuse injury to help us illustrate this point.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (Runner’s Knee)

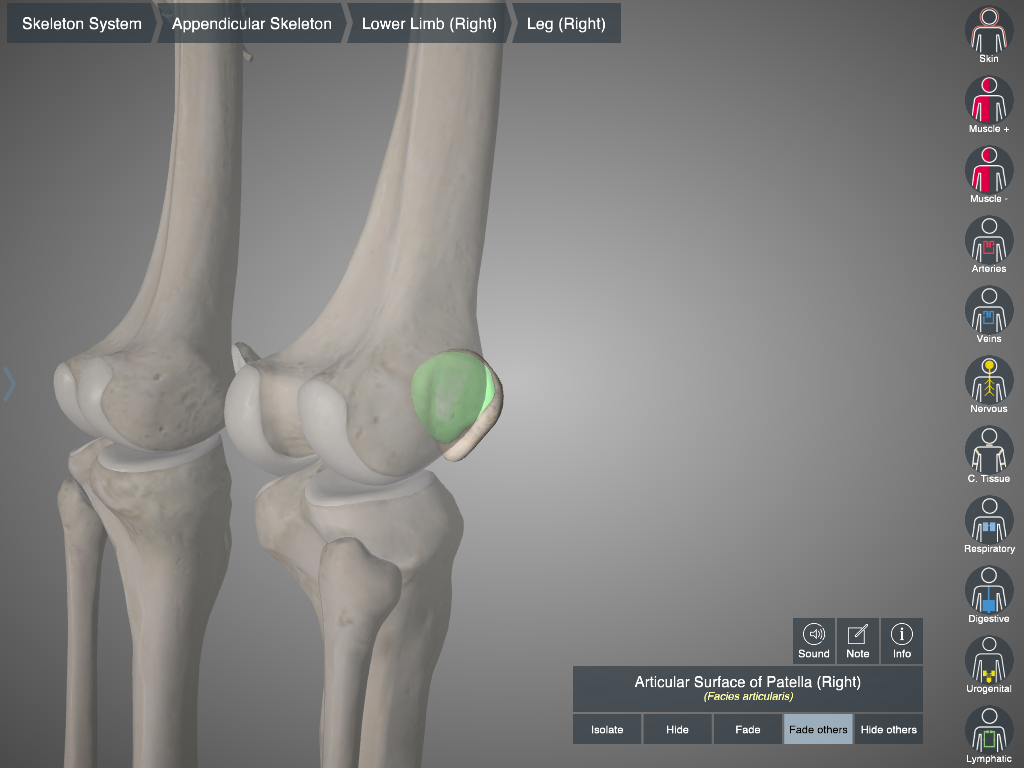

Runner’s knee is by far the most common running overuse injury (hence the name). It is experienced as a vague pain in the front of the knee or sometimes “behind” the kneecap. It is the joint cartilage on the back of the kneecap that is hurting.

When we run, we place a load on the back of the kneecap with every step we take. This is quite normal. Part of the job for the cartilage on the back of the kneecap is to tolerate this load. However, if you place too much load on that cartilage in a given period (by increasing your mileage too quickly, for example) then the cartilage will become irritated and painful.

Now you have runner’s knee. If you rest completely from running then the pain will go away. Unfortunately, that cartilage on the back of the kneecap will also get weaker. You are not loading it regularly so the body thinks, “Well, I’m not going to waste energy toughening up that cartilage on the back of the kneecap because he’s not even using it anyway”. So when you rest for 3 weeks then try to run again you discover that the pain is still there, and actually comes on quicker!

So running too much irritates the cartilage on the back of the kneecap. Running too little allows the cartilage on the back of the kneecap to become weak and deconditioned. So what’s the answer? Run not too much, but not too little.

The Adaptive Zone

Finding the amount of running that is not too much and not too little will cause the cartilage on the back of the kneecap to adapt. It will become stronger and more resilient so that in the future it can tolerate more running than it did before.

In this way we are actually using running as a mechanical stimulus to cause adaptation and strengthening the cartilage on the back of the kneecap. You can apply this same principle of adaptation to any running injury: plantar fasciitis, ITB syndrome, and tendonopathy/tendonitis. All of these running injuries involve tissues that have been overloaded. You need to find the amount of running that is not so much so as to cause irritation, but not so little that you allow deconditioning. The sweet spot is just the right amount to cause adaptation and I can that the Adaptive Zone.

Now you are using running as the mechanical stimulus to strengthen the injured tissue. That is how you can use running to heal your own running overuse injuries. Now, we’re going to talk about how to do it.

Treating Your Own Injury

We’re going to stick with the example of runner’s knee to keep things simple, but you can apply everything we’re talking about here to any overuse running injury. In my previous article on Adaptation, we talked about an imaginary runner called Dave. Dave has developed runner’s knee because went for a 20k run when he had been taking it easy for a few weeks over the holidays.

Let’s say Dave has just got home from that 20k run and his knee is feeling a little sore. A few hours later the pain feels a bit worse and he notices that it hurts when he walks down stairs. The next day he tries a little run but it hurts a lot straight away. He is pretty much limping so he decides to give up and walk home.

At this point, Dave needs to let the cartilage on the back of the kneecap settle down. It’s all angry and sensitive and any significant load like running just annoys it. In this situation, Dave needs to rest for a few days from running. Very little deconditioning/weakening of the cartilage will happen in a few days and he needs to let it calm down a bit.

Dave will know it’s time to try running again when he no longer feels any pain with activities of daily living. This means that Dave no longer feels the pain on a day to day basis when going up and down stairs, sitting in a car for a while or squatting down to pick something up. When these things no longer hurt we know that the kneecap can tolerate a little bit of load.

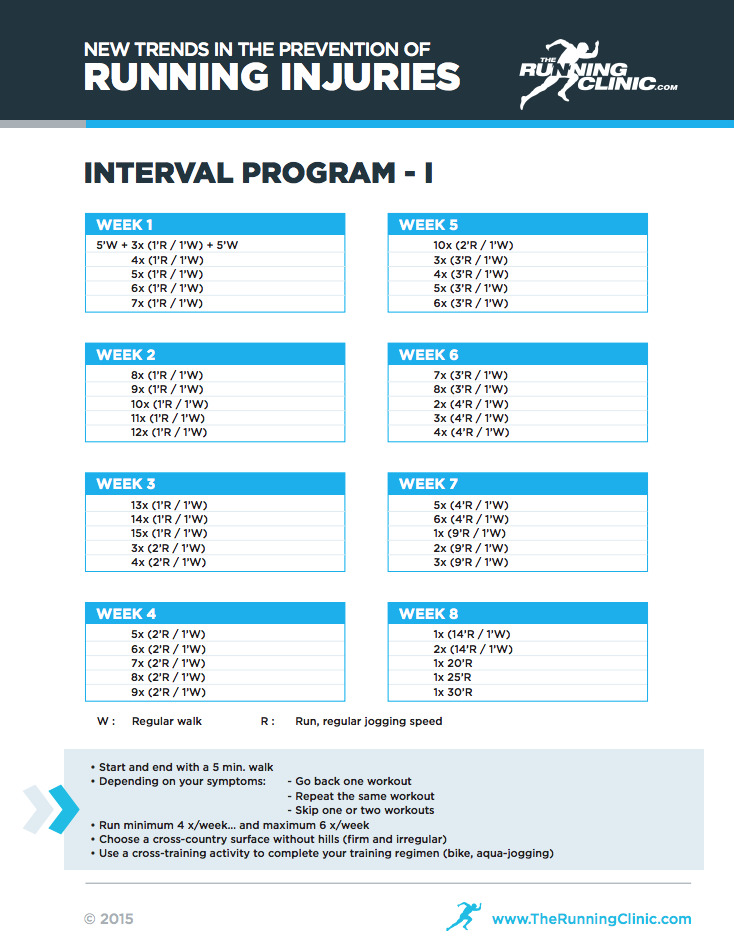

Now I’m going to ask Dave to increase the load on the kneecap a bit and see how it responds. We’re going to start him on a “Return to Running” program. These are programs for injured or beginner runners that involve short walk:run intervals. I often use one from The Running Clinic pictured below that you can download here. You can also use things like a Couch to 5k App.

The trick here is not to get wrapped up in the specific program. What we are trying to do is find the Adaptive Zone. That’s the amount of running that is not too much and not too little. Just enough to place a load on the cartilage of the kneecap to cause it to adapt. We can use one of the tools mentioned above to help us do this.

So Dave is going to do the first run of 1 minute running and 1 minute walking repeated 3 times. Or 3 sets of 1:1 run:walk intervals. I write it like this:

3×1:1

Dave does 3×1:1 no problem. Then next day he does 4×1:1. No problems there so he does 5×1:1 the next day. Dave continues in this fashion until he gets to 14×1:1. At this point Dave is starting to feel some pain in his knee. Dave now has to decide if he should continue increasing the running, reduce the running or just keep it the same. Said another way, should Dave progress, regress or plateau?

Progress, Regress or Plateau?

To help us answer this question I use the Traffic Lights System. I use the traffic lights system with clients every day to help guide decisions on pain. If you are experiencing pain with running you have to decide whether it is a red, orange or green light pain.

Red Light Pain – Regress

- The pain is really bad

- The more I do the worse the pain gets

- The pain is worse after I finish than it was when I started

- The pain is worse the following morning

Orange Light Pain – Plateau or Progress with Caution

- The pain is not that bad

- As I do more the pain is not getting any worse

- When I finish, the pain is no worse than it was when I started

- The next day, the pain doesn’t feel any worse than it did the day before

Green Light Pain – Progress

- There is no pain

- The pain is so minimal it barely registers

If any of the bullet points in the red light pain section describe your symptoms, then you need to regress. That means do less running (not no running). If any of the bullet points in the orange section (and none in the red) describe your pain then you need to plateau or progress with caution. To plateau means you can continue to do that amount of running but not more. You may also choose to progress with caution if you feel comfortable doing so. If any of the bullet points in the green light section (and none in the orange or red) describe your pain then you should progress. That means you should do more running.

Back to Dave

So Dave is up to 14×1:1 (14 sets of 1 minute running and 1 minute walking). He is experiencing pain in his knee again. He describes the pain as “not that bad, it just hurts a bit towards the end of the run, but then it goes away”. Dave is describing an orange light pain so he can go ahead and progress with caution onto 15×1:1.

Dave continues with the program. He is feeling some pain in his knee on every run but he is confident that they are orange light pains so he continues to progress with caution. When he reaches 8×3:1 (8 sets of 3 minutes running with 1 minute walking) he starts to experience more pain. It’s making him limp a bit during the run and then it’s sore to walk down stairs the next day. This is a red light pain so Dave takes a couple of days off and then regresses his running back to 5×3:1. He does 5×3:1 for a few runs and it’s feeling good so he starts increasing again. The next time he does 8×3:1 it feels ok so he continues to progress through the program.

After a few more weeks Dave gets up to 30 minutes of continuous running. His knee pain is still there but very mild now, only just in the orange light section. Dave continues to slowly increase his runs and always pays attention to his symptoms. He goes up to 32 minutes running the following week, then 35, then 40. His knee is not hurting at all with the 40 minute runs (green light) so he starts to introduce a little fast running. He does some slightly faster paced intervals of 3 minutes during his 40 minute runs. These feel ok so Dave tries a 20 minute tempo run which feels fine. The next week he does some hill intervals. These bring on an orange light level of pain so Dave doesn’t add too much to the hill workout the following week. Dave is now starting to build up the distance for his long run and can do 60 minutes without any pain at all. Dave is now getting back onto his training program and feeling confident for the upcoming race.

So what happened here?

Dave used the return to run intervals program to find an amount of running that loaded the back of his kneecap not too much, but not too little. He found the amount of running that placed a load on his kneecap within the Adaptive Zone. In response, the cartilage on the back of Dave’s kneecap adapted to the load and became stronger and more resilient. The cartilage was able to tolerate more and more load (in the form of running) as the weeks passed.

The goal for your own running injury is to find the amount of running that places a load on the injured tissue that is within the Adaptive Zone. Whether you are having trouble with the plantar fascia, your ITB, your Achilles tendon or whatever tissue you have injured. Not too much, not too little. That is the Adaptive Zone and that is the key to healing your own running overuse injury.