The term runner’s knee usually refers to pain coming from the back of your patella (kneecap). The medical term is patellofemoral pain. Pain usually comes on during longer runs but can come on sooner if the problem gets worse. Runner’s often describe pain as coming from “behind the kneecap” but it can also be felt as a relatively vague pain around the front of the knee.

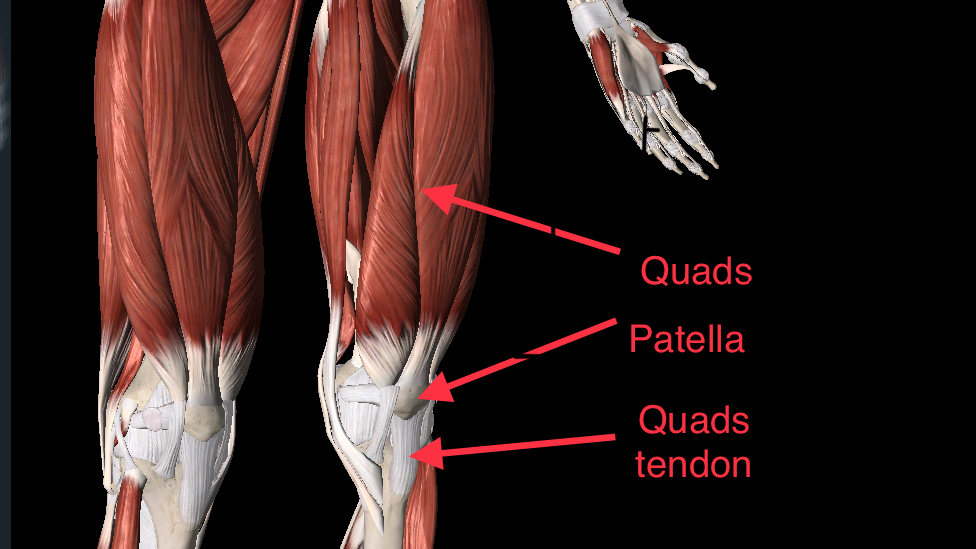

The patella (kneecap) is a sesamoid bone within the quadriceps (thigh) muscle tendon. A sesamoid bone is basically a small piece of bone living within a tendon. A tendon is the strong connective tissue that attaches our muscles to our bones. Muscles become tendons before they attach to bones.

We have a patella because as the knee bends the quadriceps tendon is bent around the femur (thigh bone) and this squashes the tendon up to the bone. If we didn’t have a patella the tendon would fray and break. Nature gives us this natural barrier in the form of the patella to prevent the tendon from being damaged.

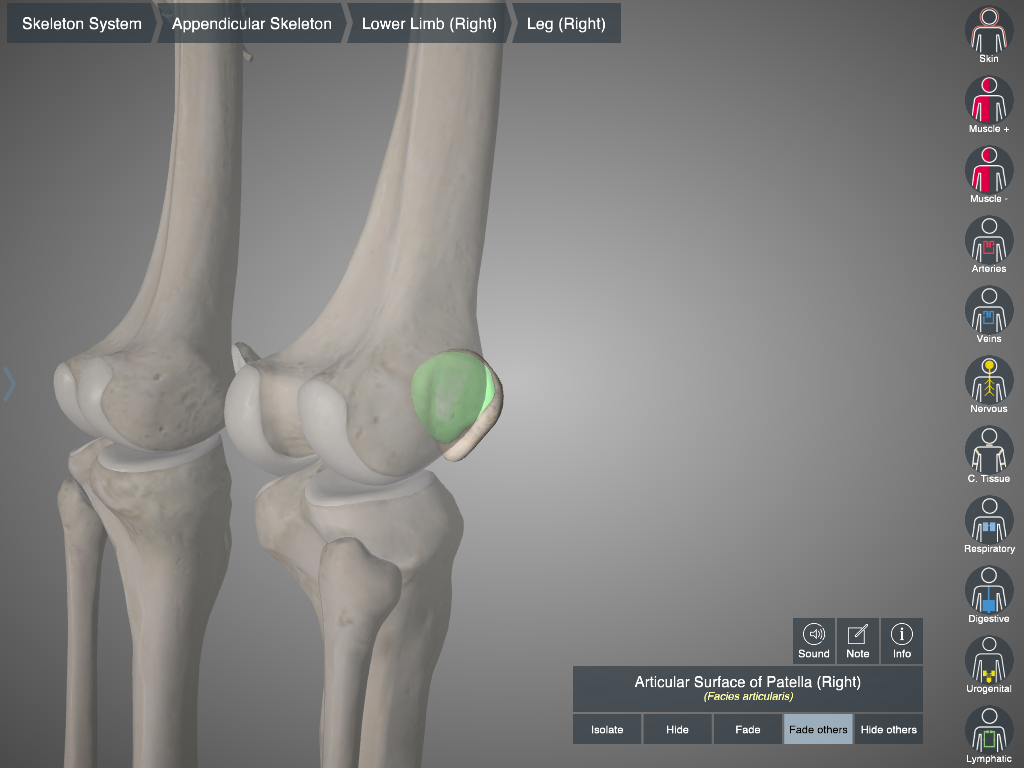

In this way the patella protects the quadriceps tendon by pressing up against the femur when the knee bends (so the tendon doesn’t have to). The back of the patella has an articular surface that pushes up against a similar articular surface on the femur. We call the articulation (interaction) between the patella and the femur the patellofemoral joint. When you bend your knees while standing, walking or running you cause the patella to push up against the femur. We call this loading the patellofemoral joint.

Where is the pain coming from?

It is the articular surface on the back of the patella that is the source of the pain if you have developed runner’s knee (patellofemoral pain). When the articular surface on the back of the patella is loaded more than it can adapt to in a given period it becomes sensitive and painful. Because this happens due to the loading of the back of the patella on the femur we call it patellofemoral pain or patellofemoral pain syndrome. When you load a tissue more than it can adapt to and it becomes painful we call it overloading the tissue.

Why do I have Runner’s Knee?

Runner’s knee is a running overuse injury. Simply put the patellofemoral joint has been overloaded, meaning more load has been placed on the patellofemoral joint in a given time than it is able to adapt to. To answer the question “Why do I have runner’s knee?” we have to ask “What are the factors that could lead to overloading of the patellofemoral joint?”.

Let’s look at the factors that could lead to runner’s knee (aka overload of the patellofemoral joint) one at a time in descending order of importance. We’re going to start with the most important factors and work down to those least important. Here’s a list of the most important things to consider if you have developed runner’s knee:

- Adaptation & Training Errors

- Running Technique

- Strength

There are other factors to consider, however, these are the factors that currently have the most evidence behind them according to recent reviews of all of the research done on runner’s knee (Barton 2017, Willy 2016). Many other things are often proposed as factors in developing runner’s knee such as foot pronation, patella maltracking, muscle imbalance, muscle tightness etc. Currently, there doesn’t seem to be as much robust evidence to support these things as being important so we’re going to stick to the three factors mentioned above. As a Physiotherapist, there are other factors I focus on with some clients, however, the three factors above are things I focus on with all clients suffering from runner’s knee.

How to Treat Runner’s Knee

Contributions to Runner’s Knee: Adaptation & Training Errors

As we discussed above, runner’s knee is pain coming from the articular surface on the back of the patella as a result of overloading. Overloading means applying too much load to a tissue in a given time frame (in this case the articular surface on the back of the patella). Loading simply refers to anything that places mechanical stress on the back of the patella. In our case, running is placing a lot of stress (load) on the back of the patella on a regular basis.

A common cause for developing runner’s knee is increasing your training volume or intensity too quickly. This increases the load on the patellofemoral joint quicker than it can adapt to meet the demand. This causes overloading of the patellofemoral joint resulting in pain and irritation (runner’s knee). However, many runner’s develop runner’s knee even when their training volume has been relatively steady. This may be a case where the load has stayed the same but the body has not. This is too big a topic for this article but you can read more about that in my article 10 Unusual Ways to Prevent Running Injuries.

To keep the patellofemoral joint healthy you need to load it regularly, not too much and not too little. If you do this the patellofemoral joint will adapt and become stronger. It will then be able to tolerate more load in the future. If you underload the patellofemoral joint it will get weaker. If you overload the patellofemoral joint it will become sensitive and painful. The trick is to find an amount of load (running) that is not too much and not too little. This is the principle of Adaptation.

I talk in much more detail about this principle in my article Adaptation: The Secret To Running Injury Prevention and Treatment. If you are really serious about addressing runner’s knee I recommend you read that article. Alternatively, here’s a video where I explain the concept:

Once you understand adaptation, you are well on your way to addressing your runner’s knee problem. You can then start to figure out how much running you are able to do that will not underload (weaken) or overload (irritate) the patellofemoral joint. I’ve written a lot more about how to do this in what I call my Load Management Series:

- Adaptation: The Secret To Running Injury Prevention and Treatment

- How to Use Running to Treat Overuse Injuries

- Cross Training for Injured Runners

- Runner’s Mechanical Load Scale

- How to Track Your Runs to Prevent Running Injuries

Contributions to Runner’s Knee: Running Technique

“Bad” running technique can not cause runner’s knee all on it’s own and it is never the only factor to consider. However, certain ways of running do place more load on the patellofemoral joint. This may increase your chances of overloading the patellofemoral joint and developing runner’s knee.

The three most relevant running technique errors that could contribute to overload of the patellofemoral joint are low cadence, over striding and running with knock knees. We’ll go through them quickly here but you can check out the following articles for a more in depth dive and some tips on how to address them:

- How to Use Running Cadence to Avoid Injuries

- Over Striding – Is it Bad for Runners?

- Running with Knock Knees

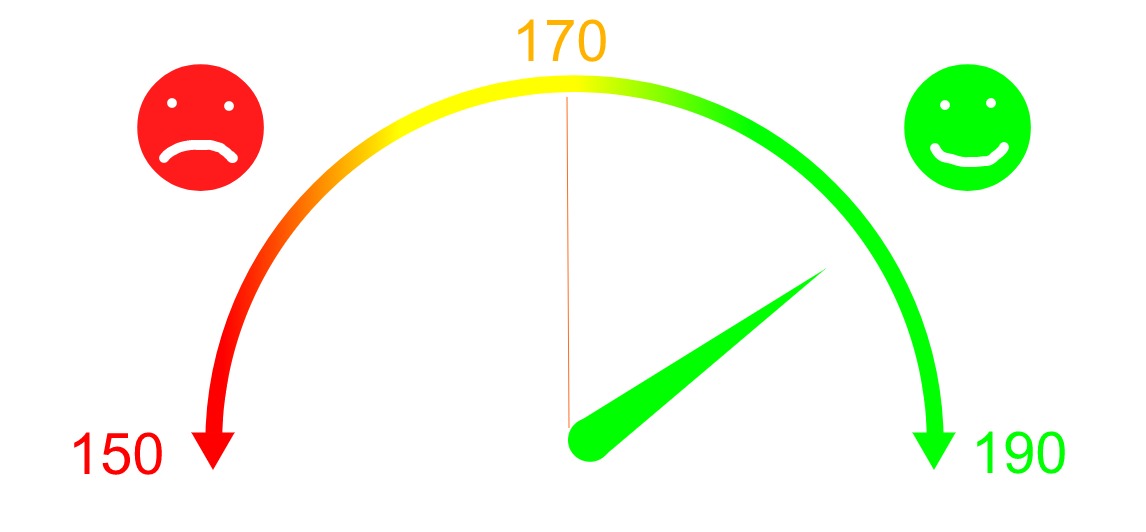

Running Cadence means how many steps you take per minute as you run. We want to have a running cadence between 170 and 190 steps per minute in what I call The Happy Zone of running cadence. Increasing your running cadence by as little as 5-10% has been shown to reduce loading at the patellofemoral joint by 10-20% (Willson 2015).

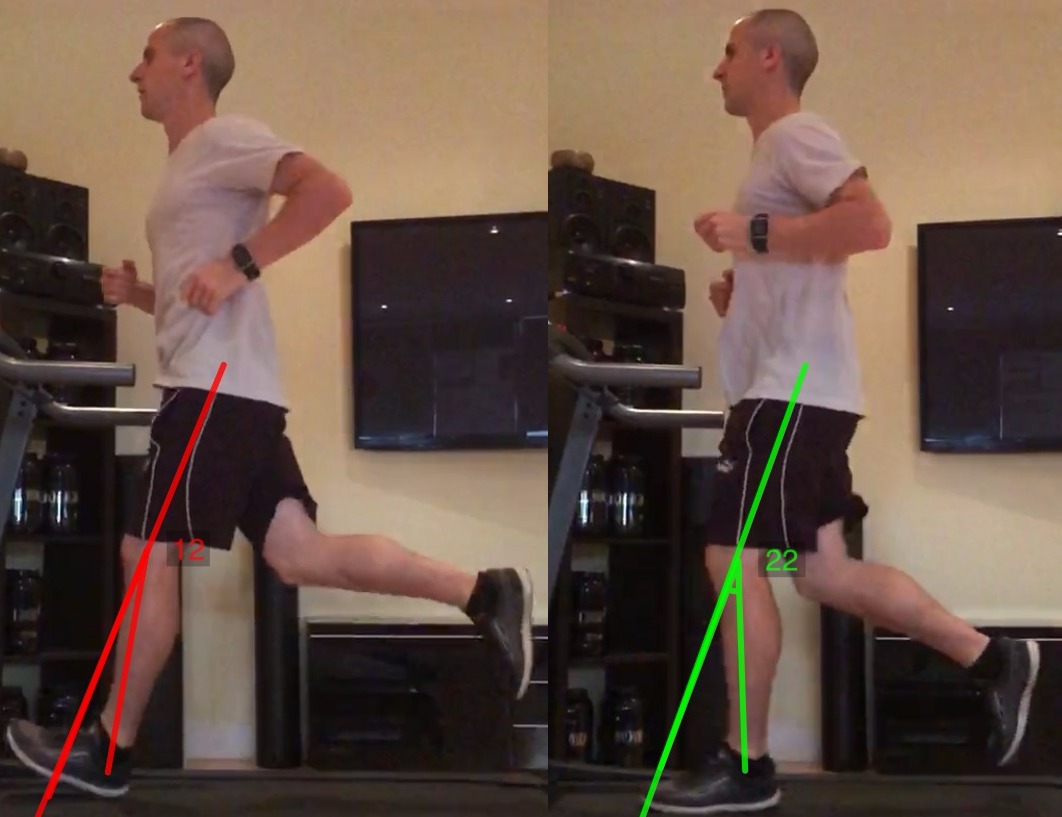

Overstriding means landing with your foot out too far out in front of you. This usually makes you land with your knee more straight. Have a quick stand up and jump up and down a little. Now do very little jumps but keep your knees straight. You’ll feel a jolt of impact as you hit the ground. That is because you didn’t bend the knees to cushion the impact. In effect, you hit the ground harder. In the research this is known as landing with a higher vertical loading rate which has been associated with developing runner’s knee (Davis 2015).

Running with knock knees means that your knee brush together as they pass each other when you run. This is often the result of the femur (thigh bone) rotating inwards and adducting on the standing leg while the pelvis on the swinging leg drops down. Think of the knee as kind of collapsing a bit on each step. This combination of internal rotation and adduction is known as dynamic knee valgus and is believed to concentrate the loading on the back of the patella into a smaller area. This increases the patellofemoral joint load by distributing the force over a smaller area (think walking in deep snow in regular shoes vs snowshoes) (Willy 2016).

Contributions to Runner’s Knee: Strength

When you go digging into the research on how strength and weakness might contribute to developing runner’s knee the water gets pretty muddy pretty quickly. To try and keep things simple I’m going to stick to what has pretty much been scientifically established and stay away from the stuff where there are still lots of questions to be answered.

We know a couple of things pretty convincingly. Strengthening your quadriceps (thigh muscles) and your glutes (hip muscles) are effective treatment strategies for runner’s knee (Lack 2015). It’s not clear which helps more or how to do it specifically. So we’re going to keep it simple.

To get stronger you need to load those muscle groups. We can do that in lots of ways but I’m going to outline a pretty simple program. You can start with bodyweight but I encourage you to go as heavy as you are able with these exercises. You are going to do 3 sets of 8 reps and I want the weight you use to be so heavy you don’t feel like you could do 10 reps. It is ok if you experience pain with these exercises as long as the pain is tolerable and goes away as soon as you finish.

We are going to use 3 exercises; the split squat, the quads curl (seated knee extension) and the crocodile. You’re going to do 3 sets of 8 reps of each exercise at least 3 times a week. Use as heavy a weight as you can. If you don’t have access to a gym do the exercises using just your bodyweight but do more reps and more often. You could do 4 sets of 20 reps of each every day for example.

Split Squat

- Stand about a foot away from a bench or chair and put your back foot up on the bench

- Have the top of the foot touching the bench

- Dip down taking the back knee towards the ground

- Keep 80-90% of your weight on the front foot

- Push up through the heel of your front foot

- Hold heavy dumbbells in your hands to add weight

The split squat is pretty puch my favourite strength exercises for runners. It will focus the strengthening effect to the glutes, hamstrings and quads. It will also strengthen your back, core and arms. It’s awesome. Doing a single leg exercise such as a split squat as opposed to a regular squat is better for runners as it will help you work on your balance as well as force you to use your weaker side (everyone has one). The split squat is a compound exercise, you strengthen a lot of things at the same time.

Quads Curl (Seated Knee Extension)

- Sit on the quads curl machine

- Adjust the backrest forwards or backwards until your knee joint is at the “hinge” part of the lever arm

- Adjust the foot/leg pad until it is in a comfortable position just above your ankles

- Fully extend your legs against the resistance

- Lower the weight down slower than you lifted it up

The seated knee extension (or quads curl as I call it) has been getting a lot of stick in recent years. I’m not going to dig into the “is it good or is it bad?” debate. My philosophy on this is that there are no bad exercises. As long as you know exactly why you are doing something and the exercise will have the effect you desire then it is appropriate. In our case, we want stronger quads. Isolating the quads using this machine stops us using our other leg muscles to compensate for quads weakness (which you could do during the split squat for example). In this way, we use the quads curl as an isolated exercise to target a specific muscle deliberately.

Crocodile (Side Plank with Leg Raise)

- Lie on your side propped up on your elbow

- Lift yourself up into a side plank (or half side plank to your knee)

- Straighten your top leg out

- Lift the top leg up and down in a sideways motion

I call this the Crocodile as the legs moving up and down is like a crocodile’s mouth opening. Much more interesting a name than “side plank with leg lift” and I have to give the credit to an old colleague for this one. It’s a great exercise to help strengthen the glut med (hip) and lateral (side) core muscles. Strength in these muscles is important to help prevent the knock knees running technique error that I described above.

Summary

Runner’s knee is pain coming from the back of the patella because you have overloaded the patellofemoral joint. To address the problem you need to manage the amount of load you put on the patellofemoral joint. You can do this by adjusting your running and other activities so that you load the patellofemoral joint not too much, but not too little. Then the patellofemoral joint will adapt and become stronger and more resilient. In the meantime you can also work on improving your running technique so that it is a little kinder to the knees as incorporate some strength training as this has been proven to be effective in treating runner’s knee.