Have you ever had a running injury? Good, then you’re a runner.

50-80% of runners will get injured in any given year (Van Gent 2007). Running injuries are an epidemic! As a runner, this really upsets me. As a Physio, it’s really good for business.

Today we’re going to get pro-active though. We’re going to look at strategies to help you avoid running injuries. This article is for runners who ARE NOT INJURED. That’s all you runners who are enjoying pain-free, injury-free training. NOW is the time to implement these strategies. Don’t wait until you’re injured because by then it is too late!

Let’s get into the Top 3 ways to avoid running injuries.

Number 1 way to avoid Running Injuries: Track your Training Load

The number one cause of running injuries is training errors.

“Too Much, Too Soon.”

This doesn’t just apply to beginner runners. Any runner can do too much too soon. Even Elite athletes with 20 years of training experience. If they increase their hill training more quickly than their Achilles tendon can adapt, they will get an Achilles Tendinopathy. If they increase their weekly mileage quicker than their IT Band can adapt to the increased load, they will get IT Band Syndrome.

In fact, any repetitive stress injury by definition is a Too Much, Too Soon injury. The tissue that has been injured was put under more load than it could adapt to. Any runner looking to avoid a running injury must understand the principle of Adaptation.

“Tissues adapt and become stronger as long as the load you place on them is not greater than their capacity to adapt.”

The Number 1 way to avoid running injuries is to Track your Training Load. Essentially this means monitoring your training volume and intensity on a weekly and monthly basis. You want to make sure you are not increasing too quickly in terms of volume or intensity at any given time. Now I’m going to give you 3 strategies to help you do that.

The 10% Rule

You will often here the 10% rule referred to. This just means not increasing your running volume by more than 10% per week. It’s actually a really good rule. It’s simple, easy to remember and it helps you regulate your changes in training volume. It does have it’s limitations though. It doesn’t consider training intensity for one thing. For example, if you kept the same training volume but did all your runs twice as fast as the week before, that’s a 100% increase in training load. The other problem is that it’s too conservative for those getting back into running after a period of injury or just time off. Many runners can quite safely add more than 10% per week in those first few weeks. After a few weeks though they will reach an amount of running that is challenging to their body. I call this their “Baseline”.

Baseline is a training load that is pretty tolerable for a runner and easy to get to. It’s different for everyone. Mine is about 25K per week all at easy pace (Zones 1-2). It’s easy for me to get to that volume and intensity without following the 10% rule. After that though, I have to be much more careful. Do you know what your Baseline is? If not, you should definitely give it some thought. Next time your getting back into training after some time off, you can use it to guide you.

The other problem with the 10% rule is compound interest. Most people have heard their financial advisor or parents wax lyrical on the magic of compounding your money by investing it. It goes something like this … If you get say 5% interest per year on a $100 a month investment, in 30 years you’ll be a bezillionaire.

Compounding money is great, but not training load. If your training load is growing exponentially over 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 20 years you’re going to get a lot of injuries. This is where periodization comes in. When you’ve been running a year or two, the 10% rule is too simplistic and you need a more sophisticated annual training plan.

Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio

That’s a mouthful right! If you haven’t heard of this yet, you probably will fairly soon. The Acute to Chronic Workload Ratio is based on the work of Professor Tim Gabbot. In his research he identified a way to predict injury risk by taking the training load average of the last 3 weeks and comparing it to the current week. If you divide this week’s training load by the average of the last 3 weeks and the number is bigger than 1.3 then there is a good chance you’ll get injured (Hulin 2016).

This is a step forward from the 10% rule as it takes intensity into account. First you record Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) score out of 10 for every run and keep a record of it. You can find more information on how to determine your intensity in my article: Running Intensity Guidelines. You then multiply your RPE score by the number of minutes your run lasted to get your “Training Units” for that run. You add up all the training units for that week and that is your Training Load. You take the training load for the current week and divide it by the average training load of the last 3 weeks. If that number is bigger than 1.3 you are at a high risk of getting injured.

Easy right?

NO! It’s really difficult and complicated. I used this strategy religiously when I was training for a marathon a few years ago because I was having such trouble with injuries. It was a massive pain but it worked really well. I got through my training without getting injured. You can have a look at my spreadsheet by clicking here. If you decide you want to try this method out for yourself, you can download a template of the spreadsheet I used by clicking here.

Runners World also made a simple little calculator to track training volume using the Acute:Chronic formula. However, it doesn’t account for intensity, only mileage. You can try that out here.

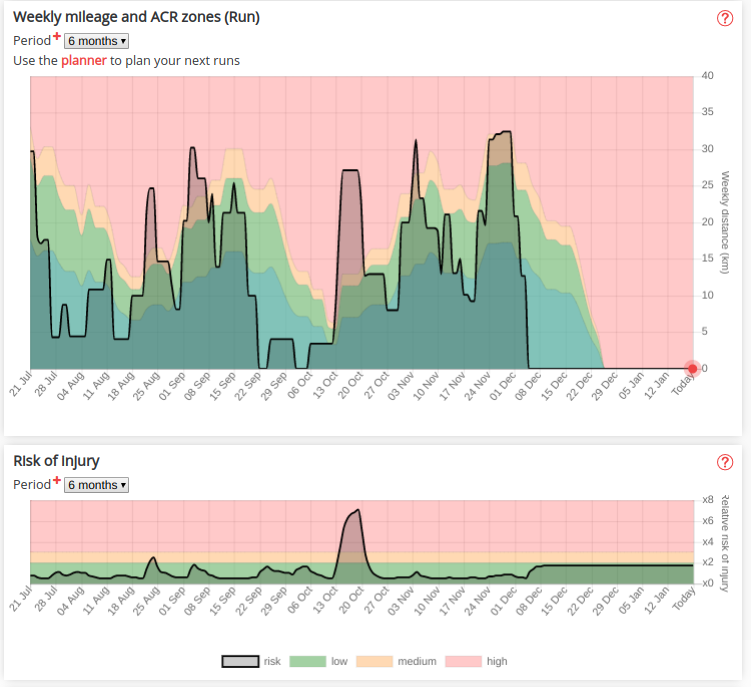

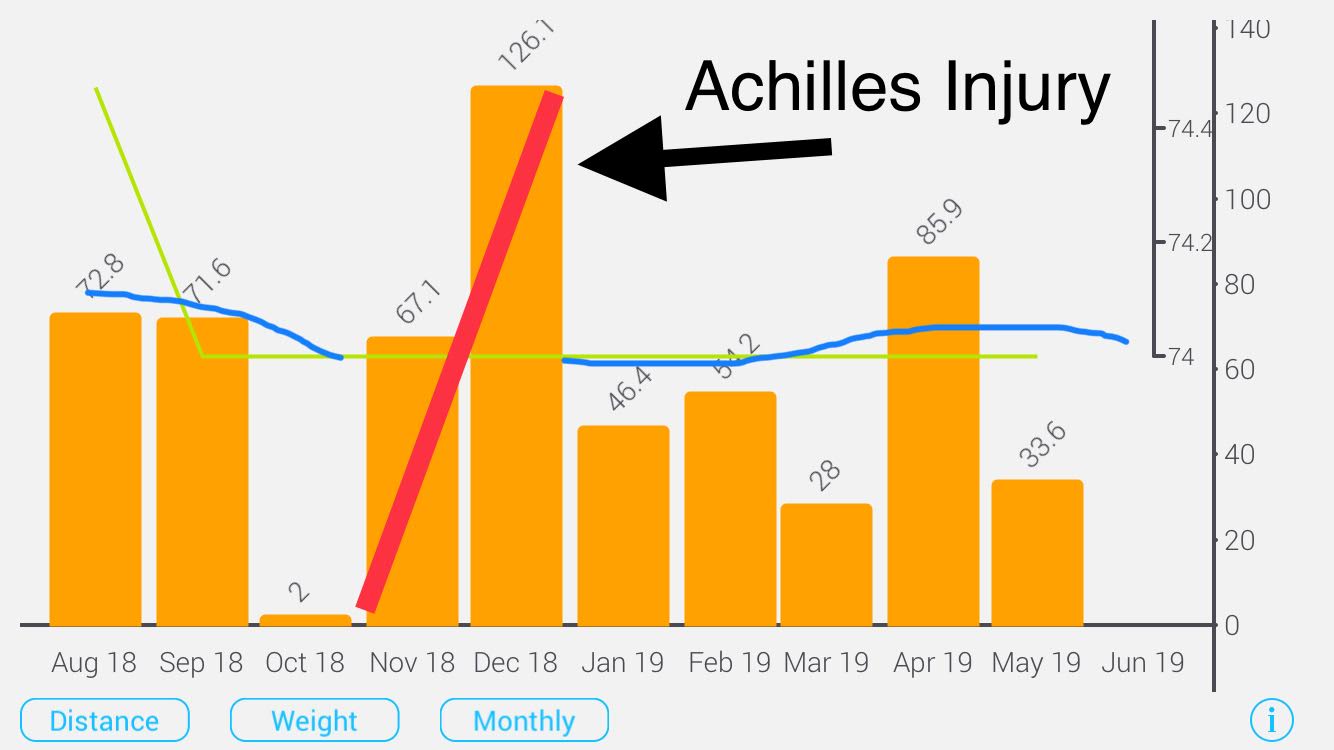

If you use Strava, you can now connect it to an app called My Training Forecast. This is a really neat little app that will display your training volume in relation to the acute:chronic workload ratio. It also gives you advice on how much it’s safe to do in the upcoming days. You can see my behaviour hasn’t been ideal in the last 6 months (ignore December, I’m having syncing issues with my GPS watch)…

Waves not Mountains

The way I personally track my training load nowadays is just to use my weekly and monthly km. It doesn’t take intensity into account but because I’m aware of that I try to make sure any time I make an increase to my training intensity I keep the volume the same that week.

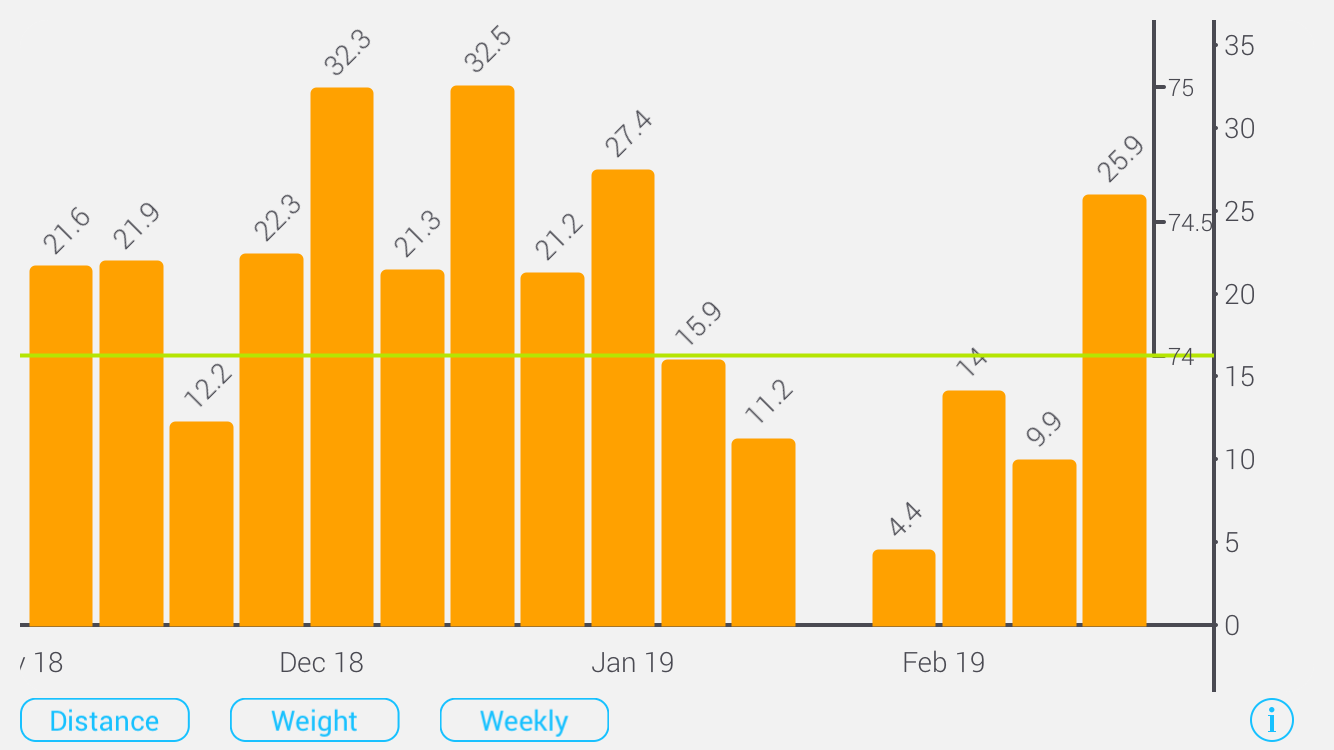

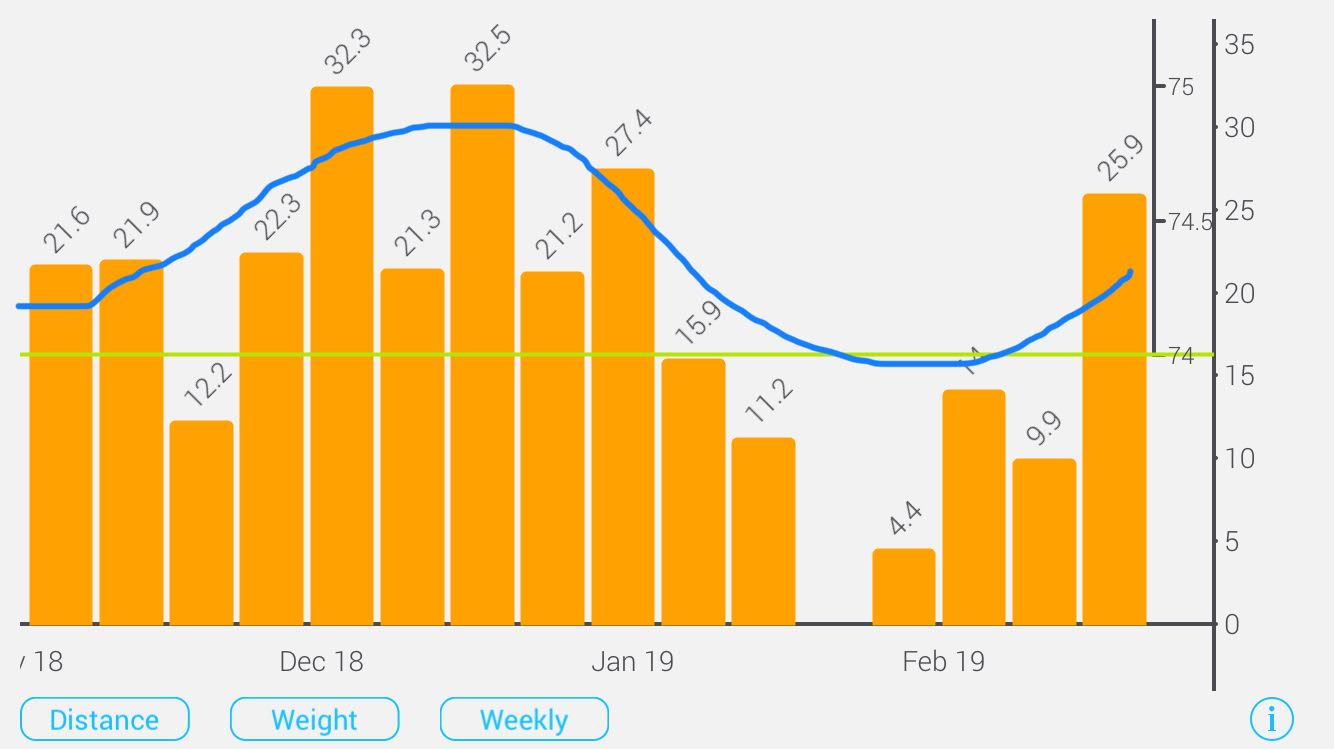

The waves not mountains strategy is super easy. At the end of every run, I turn my phone sideways and it shows me my weekly km for the last few weeks.

I use an app called iSmooth Run, which I highly recommend, but most GPS tracking apps and watches will allow you to see your weekly and monthly km somewhere.

All I’m looking for is a wavy pattern on the graph. A gentle slope up and down as the weeks pass. No big steep increases (mountains) or big steep decreases (valleys). Just gentle slopes up and down.

I’m not perfect though. In fact, I’m pretty much just as dumb as every other runner on the planet. Most recently, I’ve managed to get myself a stubborn case of Achilles Tendinopathy. When you switch into month view, it becomes pretty obvious why!

I wrote an article on this strategy so if you want to learn about it in more detail check out How to Track Your Runs to Prevent Running Injuries.

So there’s 3 strategies to help you avoid the number one cause of running injuries, Too Much, Too Soon.

Number 2 way to avoid Running Injuries: Strength Training

Adding strength training to your training schedule can help reduce your risk of developing an injury by up to 60% (Lauerson 2016). Not to mention improve your running economy by about 8% (Jung 2003). Since you are a runner, this year you have a 50-80% risk of getting injured. How would you like to reduce that risk by 60%? It’s a no-brainer right? So the only question is, how do I do it?

I’ve written a lot about strength training for runners in the past so if you want to learn more a good place to start would be:

- Strength Training for Runners in 20 minutes a week

- DIY Strength Training for Runners

- The 5 Best Kettlebell Exercises for Runners

If you really are just starting from scratch you could just do these 2 exercises once a week:

- Calf Raise 3 x 8 (Rep Max)

- Rear Lunge 3 x 8 (Rep Max)

Here’s some videos of me doing the exercises:

“Rep Max” just means the heaviest weight you can do 8 reps with. So if you do your calf raise holding a 20 lb dumbbell and get to the end and think “I could do about 5 more reps” … it’s too light. You can see in the video that I “tap out” at about 10 reps so this is a 10 Rep Max for me.

An important point here is that if you are not doing any strength training at all then anything is much better than nothing. So try and find something you enjoy or find easy to incorporate into your routine. If you want to try out bootcamp or crossfit then great, try those. If you like kettlebells use those. If you hate the gym then buy some dumbells. If you like running with other people you will probably enjoy lifting weights in a group. If you enjoy going solo then make your own plan and get on it.

Number 3 way to avoid Running Injuries: Improve your Running Technique

Improving your running technique could help reduce your injury risk. The main way it will do this is by reducing your impact forces. This how hard you hit the ground on each stride. Higher impact forces have been linked with higher injury rates in runners in the research (Davis 2015).

I’ve written a lot about Improving your running technique to reduce injury risk in the past. The three main things we want to focus on are reducing impact, increasing cadence and avoiding over-striding. I’ve written an article on these specific aspects so I’d recommend reading that:

In that article I talk about these three errors as the unhappy triad of running errors:

In order to reduce your injury risk, we want to run softly with a high cadence. If you can incorporate some work on these aspects of your technique you will be setting yourself for less injuries over the next few years.

If you want to take a deeper dive into running technique check out these articles:

- Am I a Heavy Runner?

- Over Striding – Is it Bad for Runners?

- Is Heel Striking Bad for Runners?

- Running with Knock Knees

- Running Stride Length vs. Cadence

- Discover the Running Technique Error That Could Be Causing Your IT Band Syndrome

Summary

Running injuries are SUPER common. About 50-80% of runners will get injured in any given year. Smarter training is your best way to help make sure you are not one of these injured runners missing out on the big race.

The Top 3 ways to avoid running injuries are:

- Track your Training Load

- Strength Training

- Improve your Running Technique

Work on those.

If you have any questions or comments, leave them below.

Happy Running.